In India today, a child’s despair rarely makes it past the day’s news cycle. It appears, briefly, as a headline, a trembling protest outside a school gate, or a mother’s choked plea for accountability. And then — like so much else in our hyper-aspirational society — it fades. But the children do not fade. They fall, one after another, into an abyss we refuse to confront.

November 2025 has already been a devastating month. Four students under the age of 18 died by suicide — in Delhi, Rajasthan, and Madhya Pradesh — leaving behind notes that read like indictments of a system that has normalised pressure, ridicule, bullying, and institutional neglect. The stories are harrowing; the pattern unmistakable.

A Class 10 boy from St. Columba’s School in Delhi, only 16 and full of dreams of becoming a Bollywood star like Shah Rukh Khan once was, took his life by jumping from the Rajendra Place Metro Station. His handwritten notes — found in his school bag — begged for action against teachers who he said humiliated him for months. He apologised to his family. He asked that his organs be donated. And he wrote: “My last wish is that action is taken against them; I don't want any other child to do what I did.”

But his was not the only voice. A nine-year-old girl in Jaipur leapt from her school building after 18 months of bullying and verbal abuse, ignored consistently by her teachers. Two intermediate girls in Hyderabad — one from Sri Chaitanya Junior College and another from Pragati Junior College — died on the same day under separate circumstances, one in her hostel, one at home. Just last month, another intermediate student, P. Akash Krishna, died by suicide after locking himself in his room; his father had to break down the door.

Across cities, states, and institutions, the pattern repeats: agony, isolation, unchecked bullying, insensitive responses, and an education system that equates obedience with excellence.

And then there is KIIT University in Bhubaneswar — now under severe scrutiny after three suspected suicides in under a year.

KIIT’s Tragic Year: Three Suicides and a Storm of Questions

On a Sunday night in November, 18-year-old Rahul Yadav, a first-year Computer Science student from Raigarh, Chhattisgarh, was found hanging in his KIIT hostel room. It was nearly 10:45 pm when the police were alerted. His room was locked from the inside. He became the third student the university lost in a year, after two Nepali girl students died by suicide earlier in February and May.

Rahul’s mother had repeatedly informed the university about her son’s fragile mental health. Her calls on the day of the incident went unanswered. She asked the question on everyone’s mind: “In Kota, they have anti-suicide fans in hostels. Why not here?”

She demanded strict action, alleging the authorities failed to act when warned.

Her grief amplifies more systemic questions:

-

Was Rahul offered counselling?

-

If yes, how frequently and with what follow-up?

-

Does KIIT have a mental health intervention system?

-

If it exists, why did it not prevent a preventable death?

While police suspect that complications in a personal relationship may have been a trigger, the larger point remains: student suicides are not inevitable tragedies; they are preventable failures.

Psychiatrist Dr Samrat Kar underlined this sharply: when someone is already expressing suicidal thoughts, “counselling is not enough; medication is required.” He added that the condition is treatable, and “life could have been saved.”

Yet, nothing was in place to save this life.

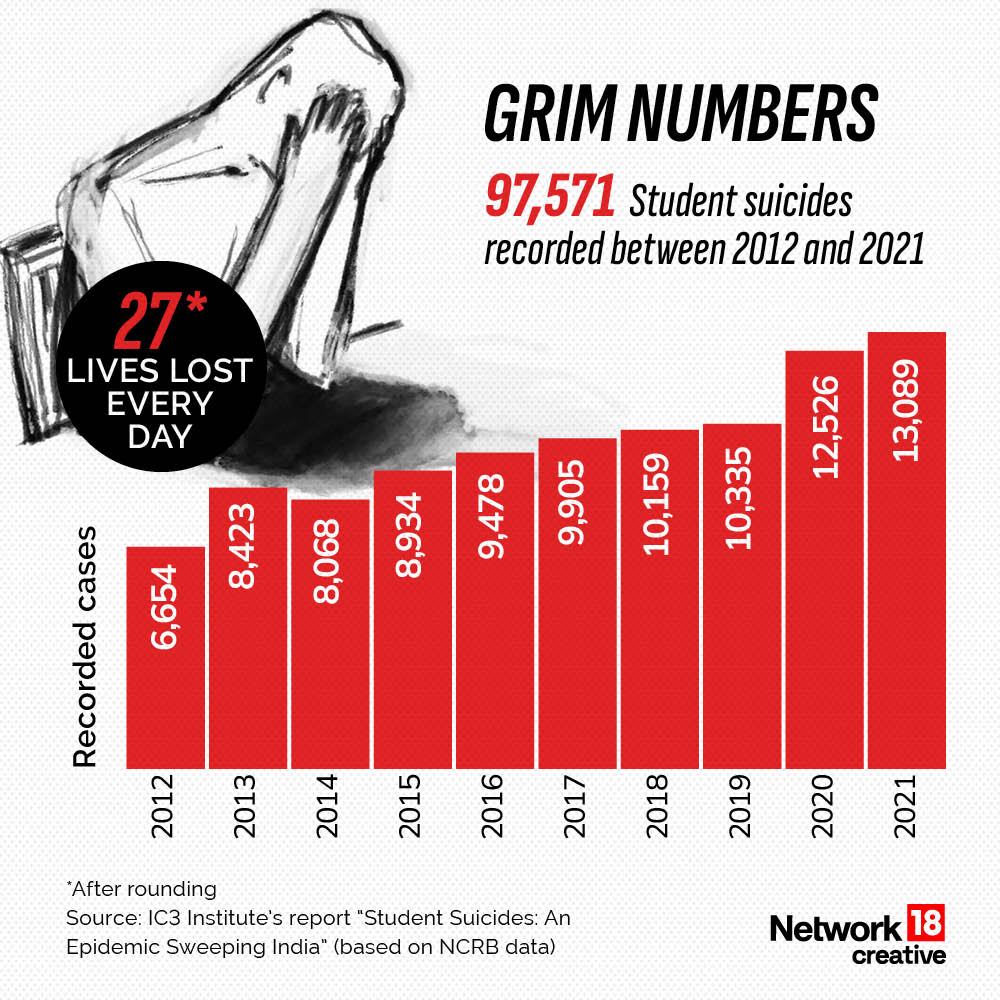

A Nationwide Crisis, Not a Series of Isolated Incidents

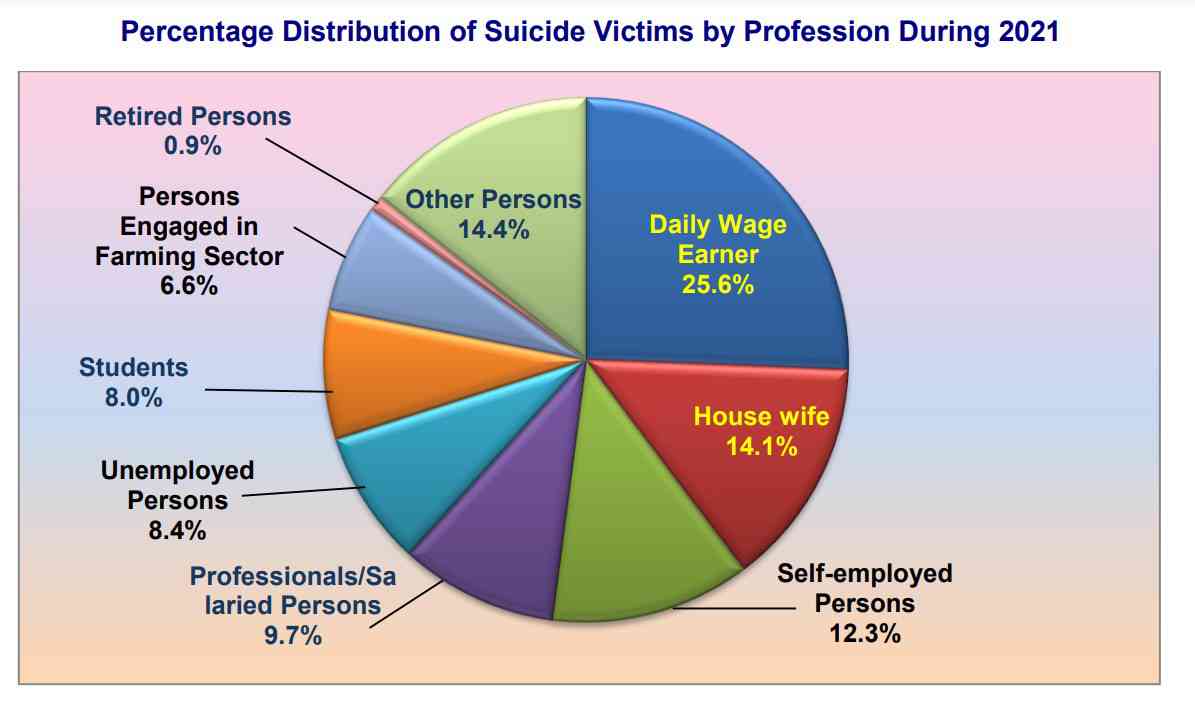

Across India, student suicides are rising at a pace that should terrify every policymaker, parent, and educator. The numbers speak for themselves:

-

13,892 student suicides in 2023

-

13,044 in 2022

-

13,089 in 2021

-

12,526 in 2020

These represent a 65% surge over a decade, rising from 8,423 suicides in 2013. Suicide is now the second leading cause of death among young people aged 15 to 29. Yet the children we lose rarely get more than a day’s attention.

In March 2025, the Indian Supreme Court set up a national task force on student mental health. It launched a massive online survey to assess the scope and nature of student distress, aiming to reach all 4.3 crore enrolled students across 60,000 institutions.

But as of now, only 6,357 institutions have responded. Fewer than 7 lakh students have filled the forms. The deadline, originally October 31, had to be extended to December 15 because participation stood at a paltry 10%.

The states worst hit by student suicides — Maharashtra, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Telangana, Bihar, Chhattisgarh, West Bengal, and Odisha — have some of the poorest participation rates. Members of the task force warn that without complete data, policy recommendations will be diluted, reforms weakened, and the crisis will continue unchecked.

Clinical psychologist Vandana, who has worked extensively with school and college-age students, stresses the urgency: students often impose crushing pressure on themselves even when parents or institutions do not. Those who cannot manage this pressure are at higher risk of suicidal thoughts. Early interventions, she says, save lives.

Institutions must acknowledge the problems their students face, she insists. Silence only deepens stigma. And stigma kills.

The Role of Technology, Alienation, and Social Isolation

The crisis, however, is larger than just academic pressure. It is social, cultural, technological, and deeply human.

A recent study published in the Asian Journal of Psychiatry paints a sobering picture:

-

70% of students report moderate to high anxiety

-

60% show signs of depression

-

70% experience elevated distress

-

18.8% have considered suicide at some point

-

12.4% have considered it in the past year alone

-

6.7% have attempted suicide

A society that once nurtured children in communities now leaves them to be raised by screens. A recent report shows that digital platforms — social media, gaming, video streaming — now dominate phone usage, accounting for 70% of the average five hours Indians spend on their phones daily.

Open spaces have vanished. Playgrounds are encroached. Families spend evenings not talking but doom-scrolling. Children mimic adults; adults, too, find escape in screens. Socialisation has collapsed.

During fieldwork from 2020 to 2023, researchers observed families in slums being held “ransom” by children demanding tabs or phones — sometimes for schoolwork, sometimes not. Schools simultaneously promote online platforms and warn about screens, creating a cycle of dependence and fear.

Excessive gadget use is causing physical harm, too; experts warn of spine misalignment in children. More crucially, it results in a profound socialisation deficit: a shrinking ability to express, feel, and connect.

This alienation feeds into anxiety. Anxiety feeds into despair. Despair, when ignored, leads to tragedy.

The Culture of Aspirational Brutality

The tragedy at St. Columba’s School struck a particularly deep chord because it reflected a broader societal rot: India’s hyper-aspirational culture is crushing its children.

We tell them:

-

Excel at all costs.

-

Don’t question adults.

-

Don’t express weakness.

-

Don’t fail — ever.

Board exams are marketed as life-or-death events. Coaching centres have become factories. Schools prioritise marks over mindfulness, discipline over dialogue.

Children who are imaginative, creative, or neurodivergent are often the most vulnerable. The Delhi boy who loved dancing, dramatics, and filmmaking did not die because of a single incident — he died because a system failed him consistently.

Akash Banerjee of The Desh Bhakt captured the sentiment when he asked whether “terror teachers” are pushing students over the edge. Hundreds of comments poured in describing harrowing experiences at the hands of abusive or apathetic educators.

Not every child has supportive families, as Banerjee did. Many have no safe space at all.

A System That Responds Only After Death

After the Delhi tragedy, the school suspended three teachers and the principal. But accountability after death is not justice. It is damage control.

The same reactive approach was evident elsewhere:

-

In Hyderabad, police registered cases and began investigations only after the suicides.

-

In KIIT, questions on safety, counselling, and infrastructure came only after Rahul’s death.

-

In Kota, anti-suicide fans were introduced after a spate of suicides.

-

National guidelines from the Supreme Court came only after rising numbers became impossible to ignore.

Prevention has never been India’s strength. As a society, we wait for tragedy to force our hand.

What Must Change — And Now

India is at a breaking point. We can no longer afford to treat student suicides as isolated incidents. They are symptoms of a cultural, institutional and psychological emergency.

Here is what must happen immediately:

1. Centre mental health in parenting and pedagogy

Children do not need perfection. They need presence. Schools must become second homes, not factories producing tomorrow’s workforce.

2. Implement the Supreme Court’s 2025 guidelines uniformly

Every school must have trained counsellors, grievance mechanisms, and safe reporting channels.

3. Mandatory mental health programmes starting from primary school

Early interventions work. They build lifelong coping skills.

4. Regulate coaching centres and academic pressure

Education cannot remain a pressure cooker.

5. Dramatically scale up counselling infrastructure

India does not just lack counsellors — it lacks empathetic, trained, sensitive counsellors.

6. Hold institutions accountable for every warning ignored

If parents or students raise red flags, silence cannot be the institutional response.

7. Rebuild community and human connection

Technology must be balanced with real human interaction. Children must grow up with people, not screens.

A Cultural Shift: From Aspiration to Empathy

The most important change, however, cannot be legislated. It must be embraced.

Children are not trophies. They are not rank-holders. They are not extensions of parental dreams or societal expectations.

They are human beings — fragile, hopeful, vulnerable — and they are telling us, in their final notes, that we are failing them.

We must listen. Because if we do not change course now, we will continue to lose our children not to incapacity, but to indifference.

With inputs from agencies

Image Source: Multiple agencies

© Copyright 2025. All Rights Reserved. Powered by Vygr Media.