In a landmark judgment that reaffirms the fundamental values of human dignity and constitutional justice, the Supreme Court of India has ordered the phased but complete abolition of hand-pulled rickshaws in Matheran, Maharashtra. The court condemned the practice as “inhuman,” “against the basic concept of human dignity,” and a betrayal of India’s constitutional promise of social and economic justice.

The verdict, delivered by a bench headed by Chief Justice of India B.R. Gavai along with Justices K Vinod Chandran and N V Anjaria, marks a historic moment in India’s journey toward inclusive development and humane labor reforms.

The Inhuman Reality Behind Hand-Pulled Rickshaws

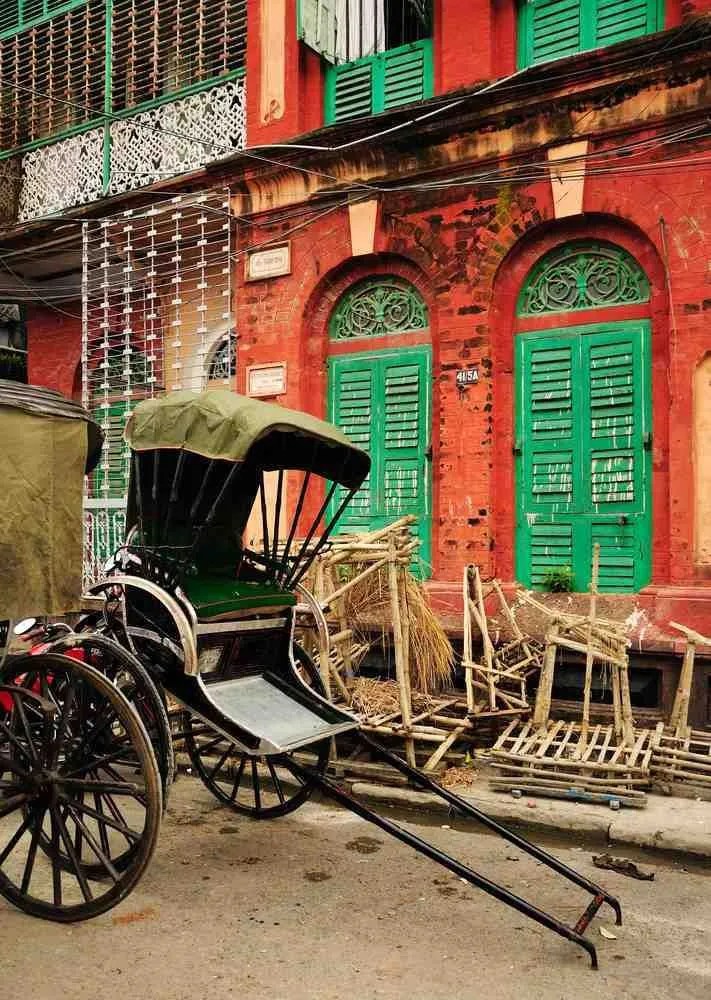

Matheran, a scenic hill station nestled in the Western Ghats and protected as an eco-sensitive zone, has long prohibited motorized vehicles. In the absence of automobiles, tourists and locals alike have depended on hand-pulled rickshaws and horse carts for transportation. These rickshaws—powered by the sheer physical labor of impoverished men—have been a haunting symbol of exploitation and human indignity.

The apex court took serious exception to the continuation of this archaic mode of transport, particularly when India is a developing nation aiming for global leadership while grounded in a Constitution that guarantees dignity, equality, and justice to all its citizens.

“It is really unfortunate that even after 45 years of the Supreme Court's judgment in the Azad Rickshaw Pullers Union case, and after 75 years of the Constitution, such a degrading practice is still prevalent,” said Chief Justice Gavai.

A Betrayal of Constitutional Promises

The Court reiterated that the practice violates Article 23 of the Indian Constitution, which prohibits all forms of forced labor—even if compensation is provided. Citing the 1980 Azad Rickshaw Pullers Union v. State of Punjab judgment, the Court emphasized that manual rickshaw pulling is inconsistent with the Preamble’s promise of social justice.

The judgment drew parallels with the case People of India for Democratic Rights v. Union of India, where the Supreme Court held that non-payment of minimum wages amounted to forced labor. The same expansive reading of Article 23 was applied here, making it clear that no individual should be compelled to earn a living through such degrading means, even if done voluntarily under economic duress.

Victims of Circumstance, Not Choice

The Court made a poignant acknowledgment: most hand-pullers do not choose this work willingly. Instead, they are victims of poverty and limited opportunities. Highlighting this, the bench stated:

“These individuals are compelled by circumstance, not choice. Allowing this practice to continue is akin to betraying the promise ‘We the People’ made to ourselves in the Constitution.”

Recognizing this reality, the Court's focus shifted not just to banning the practice but also to rehabilitating those affected, ensuring that they are not left jobless and marginalized.

The Alternative: E-Rickshaws as a Humane, Eco-Friendly Solution

With rapid advancements in technology, e-rickshaws have emerged as a clean, efficient, and humane alternative. The Court has directed the State of Maharashtra to design a comprehensive rehabilitation scheme that includes:

-

Phased introduction of e-rickshaws, replacing hand-pulled carts.

-

Licensing priority to existing hand-rickshaw pullers.

-

Adoption of the Kevadia model from Gujarat, where tribal women operate e-rickshaws on a hire basis, serving tourists visiting the Statue of Unity.

-

Leveraging Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) funds to sponsor e-rickshaw procurement.

The Court was unequivocal that lack of funds cannot be used as an excuse for failing to implement the scheme.

“We clarify that non-availability of funds cannot be an excuse for non-implementation of the aforesaid scheme,” the Court emphasized.

Guidelines and Timeline for Implementation

To ensure a smooth transition and avoid economic hardship for the rickshaw pullers, the Court laid down a set of clear and binding directives:

-

Ban to be enforced within 6 months from the date of the judgment.

-

E-rickshaw licenses to be first offered to existing hand-cart pullers.

-

The Matheran Monitoring Committee, headed by the local Collector, will:

-

Identify genuine hand-pullers.

-

Determine the exact number of e-rickshaws required.

-

-

Paver blocks may be laid on the 4 km main stretch from Dasturi Naka to Shivaji Statue to make roads motorable during monsoons—but not on internal roads or trekking routes to preserve Matheran’s eco-sensitive character.

-

All concrete blocks previously laid must be replaced with paver blocks.

-

The remainder of the e-rickshaw allotments may be distributed among tribal women and other local residents in need.

Environmental and Social Context

Matheran was designated an eco-sensitive zone by the Ministry of Environment and Forests in 2003. It is home to a rich diversity of flora and fauna, including bonnet macaques, Hanuman langurs, barking deer, and Malabar giant squirrels. The town’s ban on automobiles is crucial to preserving this fragile ecosystem.

However, this ban inadvertently perpetuated regressive labor practices, compelling the Supreme Court to balance ecological preservation with human rights and livelihood dignity.

Legal Journey and Broader Significance

The issue reached the Court through an interlocutory application in the longstanding TN Godavarman Thirumulpad environmental litigation. It originally stemmed from the Maharashtra government’s 2022 proposal to pilot e-rickshaws in Matheran.

This seemingly administrative decision spiraled into a constitutional debate, resulting in a watershed moment for labor rights and human dignity in India.

In earlier hearings, resistance came from horse-cart operators’ associations, who raised concerns about the paving of roads and e-rickshaw operations. However, the Court struck a balance—permitting minimal road modification while upholding the larger goal of human rights.

Final Thoughts

The Supreme Court’s bold, clear-sighted decision to ban hand-pulled rickshaws in Matheran is a defining moment for India’s commitment to human dignity, labor justice, and progressive governance.

This judgment is not just about one hill station—it is a clarion call for eradicating all forms of exploitative labor that still exist in modern India. By offering a sustainable, dignified alternative through e-rickshaws and demanding accountable governance, the Court has aligned India's developmental goals with its constitutional values.

“To continue such human practice even after 78 years of independence and 75 years of the Constitution would be betraying the promise given by the people of India to themselves.”

This is not merely a ban. It is a restoration of dignity, a step toward justice, and a moment of national introspection.

With inputs from agencies

Image Source: Multiple agencies

© Copyright 2025. All Rights Reserved. Powered by Vygr Media.