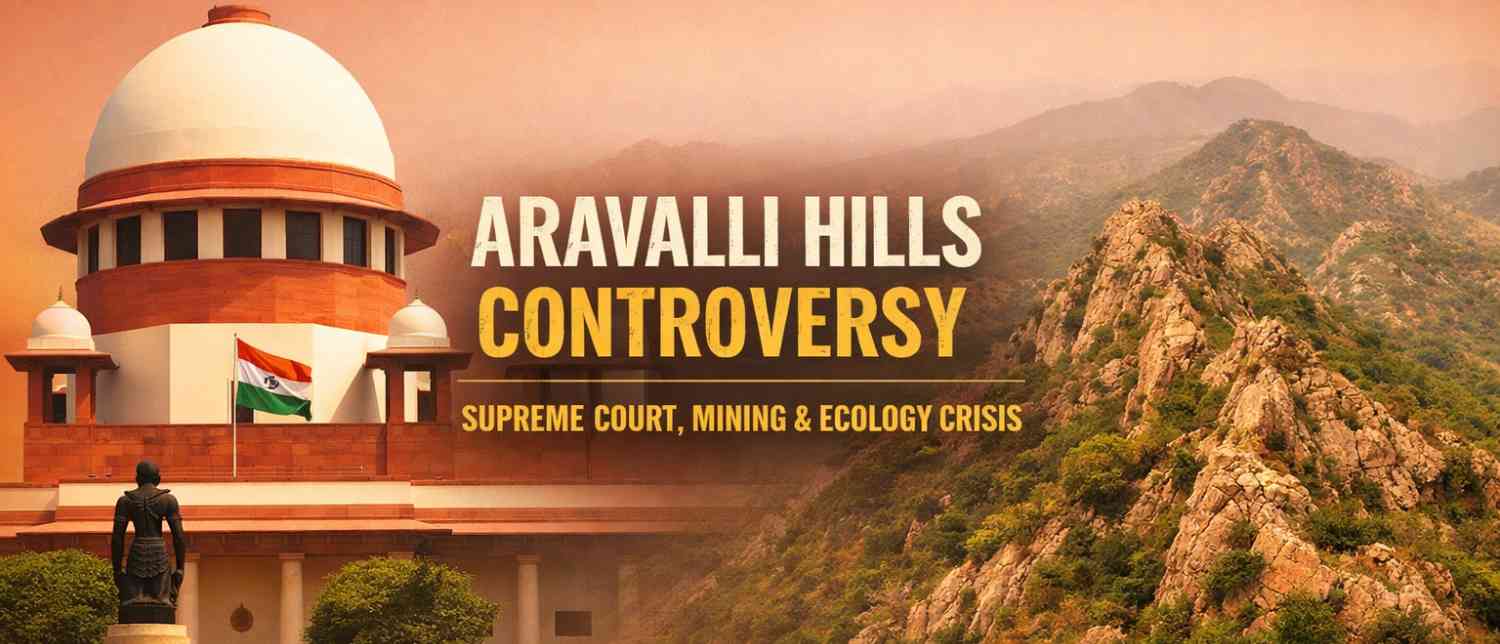

Few environmental debates in India today so starkly expose the fault lines between development, ecology, science, and governance as the controversy over redefining the Aravalli Hills. What began as a judicial attempt to bring uniformity to environmental protection has snowballed into a far-reaching national debate—one that questions not just how India defines a mountain range, but how it understands nature, progress, and its own constitutional duty to protect ecological heritage.

The Supreme Court’s decision on November 20 to accept a new, ministry-backed definition of the Aravalli Hills—followed swiftly by a stay on its own order and the proposal to constitute a new high-powered expert committee—has laid bare deep ambiguities, scientific contestations, and political contradictions. At stake is the fate of one of the world’s oldest mountain systems, a fragile ecological barrier that has shaped climate, biodiversity, and civilisation across northwestern India for nearly two billion years.

A definition with far-reaching consequences

At the heart of the controversy lies a deceptively technical question: what exactly constitutes the Aravalli Hills and the Aravalli Range?

In October, a committee constituted under the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC), chaired by the Environment Secretary and comprising representatives from Rajasthan, Haryana, Gujarat, Delhi, and technical bodies, recommended a “uniform definition” to be applied across all Aravalli states. According to this definition, an “Aravalli Hill” is any landform in designated Aravalli districts that rises 100 metres or more above its local relief. An “Aravalli Range” is defined as a collection of two or more such hills located within 500 metres of each other.

The Supreme Court accepted this definition on November 20, while simultaneously banning the grant of fresh mining leases in Aravalli areas across Delhi, Haryana, Rajasthan, and Gujarat until expert reports are finalised. The Centre subsequently claimed that the new framework would strengthen protection and ensure that over 90 per cent of the Aravalli region remains safeguarded.

Yet almost immediately, the decision triggered widespread criticism from environmentalists, scientists, civil society groups, and opposition parties. The objections were not ideological but empirical: critics argued that the new criteria—particularly the 100-metre elevation threshold and the 500-metre proximity rule—would exclude vast stretches of the Aravalli ecosystem from legal protection, potentially opening them up to mining and other disruptive activities.

Why the Aravallis matter

The Aravalli range is not just a chain of eroded hills stretching from Delhi through Haryana and Rajasthan into Gujarat. It is among the oldest geological formations on the planet, dating back nearly two billion years. Over millennia, it has acted as a natural barrier against desertification, gently redirecting monsoon winds eastwards and nurturing sub-Himalayan river systems that sustain the north Indian plains.

Historically, state governments have recognised the Aravallis across 37 districts for their ecological importance. Their role in groundwater recharge, biodiversity conservation, and climate regulation has been repeatedly underscored by courts and conservationists alike. In November, the Supreme Court itself reiterated that uncontrolled mining in the Aravallis poses a “great threat to the ecology of the nation,” necessitating uniform criteria for their protection.

This ecological significance makes the controversy over their definition far more than a cartographic exercise. It determines where mining is permitted, where environmental safeguards apply, and whether contiguous ecosystems are protected as wholes or fragmented by legal technicalities.

The numbers that sparked alarm

Much of the current unease stems from data generated by the Forest Survey of India (FSI). An internal assessment of its digitised data revealed that out of 12,081 Aravalli hills in Rajasthan that are 20 metres or higher—a height crucial for their function as wind barriers—only 1,048, or just 8.7 per cent, meet the 100-metre elevation threshold. If all 1,18,575 identified Aravalli hills are considered, over 99 per cent would fail to qualify under the new definition.

These findings, reported by The Indian Express, directly contradict the ministry’s assurance that more areas would be included under the 100-metre formula than under the FSI’s earlier 3-degree slope-based definition. That earlier methodology, used in 2010 to map hills across 15 districts of Rajasthan under Supreme Court orders, was explicitly designed to capture the full ecological extent of the range rather than just its highest peaks.

The FSI conveyed its concerns to the ministry, but the government proceeded with the 100-metre definition nonetheless. The Central Empowered Committee (CEC) distanced itself from the recommendation, writing to the court-appointed amicus curiae that it had neither examined nor approved the ministry’s proposal and reiterating that the FSI’s definition should be adopted to ensure ecological conservation.

Judicial unease and course correction

Faced with mounting criticism, the Supreme Court has now paused and reflected. On Monday, a three-judge bench led by Chief Justice of India Surya Kant stayed its own November 20 order and proposed the constitution of a high-powered expert committee of domain specialists. The stay will remain in effect until the new committee is formed, and the matter is scheduled for further consideration on January 21.

The court acknowledged a “significant outcry” among environmentalists and noted that public dissent stemmed from perceived ambiguities and lack of clarity in both the definition and the court’s own directions. Such ambiguities, the bench observed, risk creating regulatory gaps that could undermine the ecological integrity of the Aravalli region.

The issues flagged for expert examination are telling. The court wants clarity on whether restricting the Aravalli Range to hills within 500 metres of each other artificially narrows protected territory while expanding “non-Aravalli” zones vulnerable to unregulated mining. It has questioned whether hills exceeding 100 metres in elevation still form a contiguous ecological system even when separated by distances greater than 500 metres—and whether mining in these gaps would compromise ecological continuity.

Crucially, the bench has sought verification of the widely publicised claim that only 1,048 out of 12,081 hills meet the 100-metre threshold. If this assessment proves accurate, the court has asked whether an exhaustive scientific and geological investigation—entailing precise measurement of all hills and hillocks—is required to arrive at a more nuanced and ecologically sound definition.

The proposed expert review will also undertake a multi-temporal evaluation of both short-term and long-term environmental impacts arising from the implementation of the recommended definition, examine areas excluded from protection, and assess whether even “regulated” or “sustainable” mining within newly demarcated Aravalli zones could have adverse ecological consequences.

The mining question and contested assurances

The mining implications of the new definition lie at the core of the controversy. Activists and scientists have warned that redefining the Aravallis without adequate scientific assessment or public consultation risks exposing large swathes of fragile terrain across Haryana, Rajasthan, and Gujarat to extraction.

The Centre has countered these claims by emphasising the Supreme Court–ordered freeze on new mining leases and by pointing out that areas designated as tiger reserves, national parks, wildlife sanctuaries, eco-sensitive zones, wetlands, and compensatory afforestation plantations will remain protected regardless of their classification as Aravalli hills.

Environment Minister Bhupender Yadav has asserted that more than 90 per cent of the Aravalli region will remain under protection. Yet this assurance sits uneasily with his own admission, made at a press conference on December 22, that the actual extent of Aravalli areas covered under the 100-metre definition would only be known after ground demarcation is completed.

Meanwhile, earlier judicial history complicates the narrative. In February 2010, the Supreme Court had explicitly rejected Rajasthan’s “deemed definition,” which treated only hill peaks or parts rising 100 metres above ground level as Aravalli Hills. Instead, it directed the FSI, in cooperation with the CEC and the state, to assess the entire hill range using satellite imagery, without confining the exercise to peaks above a particular height.

That legacy makes the court’s November acceptance of a similar 100-metre benchmark—rejected 15 years earlier—all the more contentious.

Political fault lines and public protest

The redefinition has also ignited political confrontation. The Congress accused the Modi government of pushing through a definition that would have “very grave environmental and public health consequences” and demanded an immediate review. Senior leader Jairam Ramesh argued that the new criteria would effectively strip 90 per cent of the Aravalli Hills of their protected status, calling the Supreme Court’s acceptance of the revised definition “bizarre.”

Environmentalists and citizen groups staged protests, framing the issue not merely as a legal dispute but as a question of intergenerational justice and ecological survival.

Beyond definitions: the idea of progress

Yet the Aravalli debate is also about something deeper than metrics and maps. It reflects a larger crisis in how modern societies—India included—conceptualise progress.

As one evocative commentary on the issue argues, the attempted “takeover” of the Aravalli range under the banner of development is part of a long-running global pattern: the fusion of science and technology into a form of technoscience that delivers short-term material gains while inflicting long-term planetary damage. This worldview, rooted in a reductionist understanding of nature as inert matter to be extracted and optimised, has helped usher in the climate crisis and the Anthropocene age.

India’s predicament is particularly stark. Despite invoking ancient ethos and civilisational values, the country ranks near the bottom of the Environmental Performance Index—176 out of 180 in 2024—lagging behind neighbours such as Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and even China. Air and water pollution, biodiversity loss, deforestation, and the concretisation of sensitive ecosystems testify to a development model that counts numbers but forgets people and ecological limits.

The Aravallis, dismissed by some as 800 kilometres of dead rock, tell a different story. Official documents acknowledge that they guide monsoon clouds, feed river systems, and protect the plains. Seen through an ecological lens, they are not isolated peaks but a living, interconnected system whose value cannot be reduced to elevation thresholds and distance markers.

The path ahead

The Supreme Court’s decision to pause, listen, and re-examine is a recognition that environmental governance cannot rest on hurried definitions or administrative assurances alone. The formation of a new high-powered expert committee offers an opportunity—not just to correct technical flaws, but to re-anchor policy in ecological intelligence.

This moment calls for humility: an acceptance that scientific tools must be applied with care, that local relief and average slopes cannot substitute for holistic ecological understanding, and that development models abandoned by advanced economies in favour of sustainability cannot be resurrected in the Global South under the guise of growth.

Ultimately, the Aravalli controversy is a test of whether India can reconcile progress with restraint, extraction with ethics, and governance with wisdom. The mountains may be ancient and eroded, but the choices made today will shape the landscape—physical and moral—that future generations inherit.

With inputs from agencies

Image Source: Multiple agencies

© Copyright 2025. All Rights Reserved. Powered by Vygr Media.