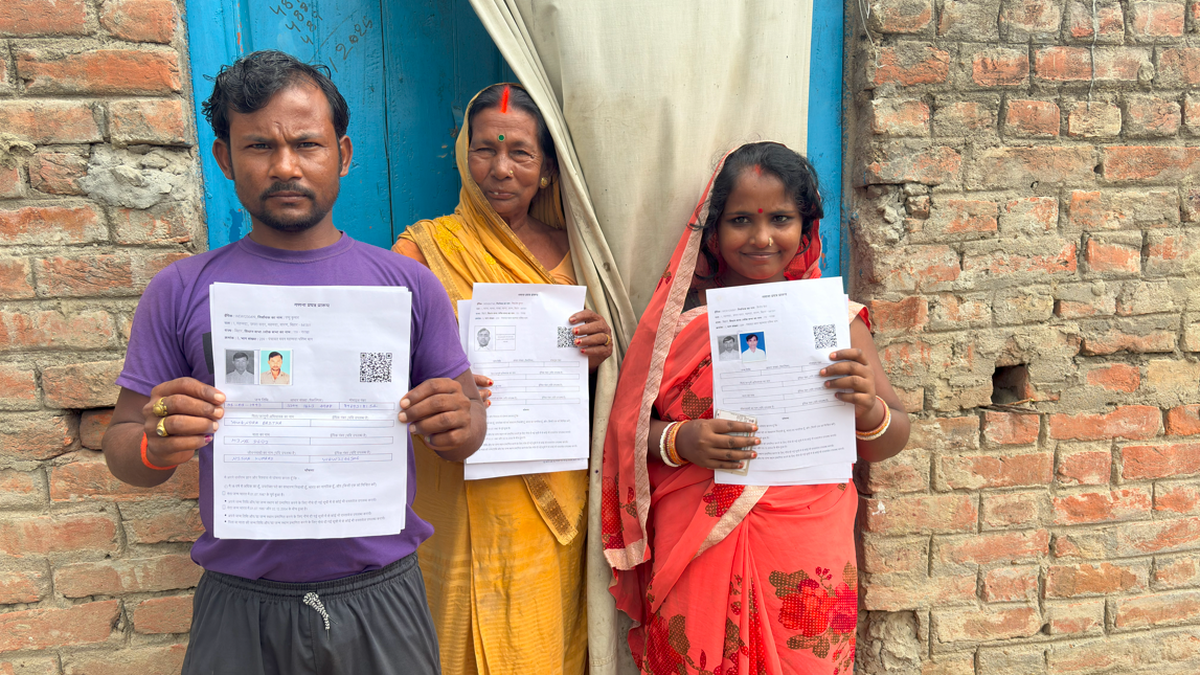

In a significant change to its voter-roll updating process, the Election Commission of India (EC) has placed the responsibility on individual voters—rather than the system—to prove their citizenship in a Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of electoral rolls for Bihar. The move, announced on June 24, departs sharply from earlier practice by treating all existing voters on equal footing with new applicants and requiring documentary evidence. It also overrides previous norms that emphasized the validity of the existing voter list.

What’s Changed?

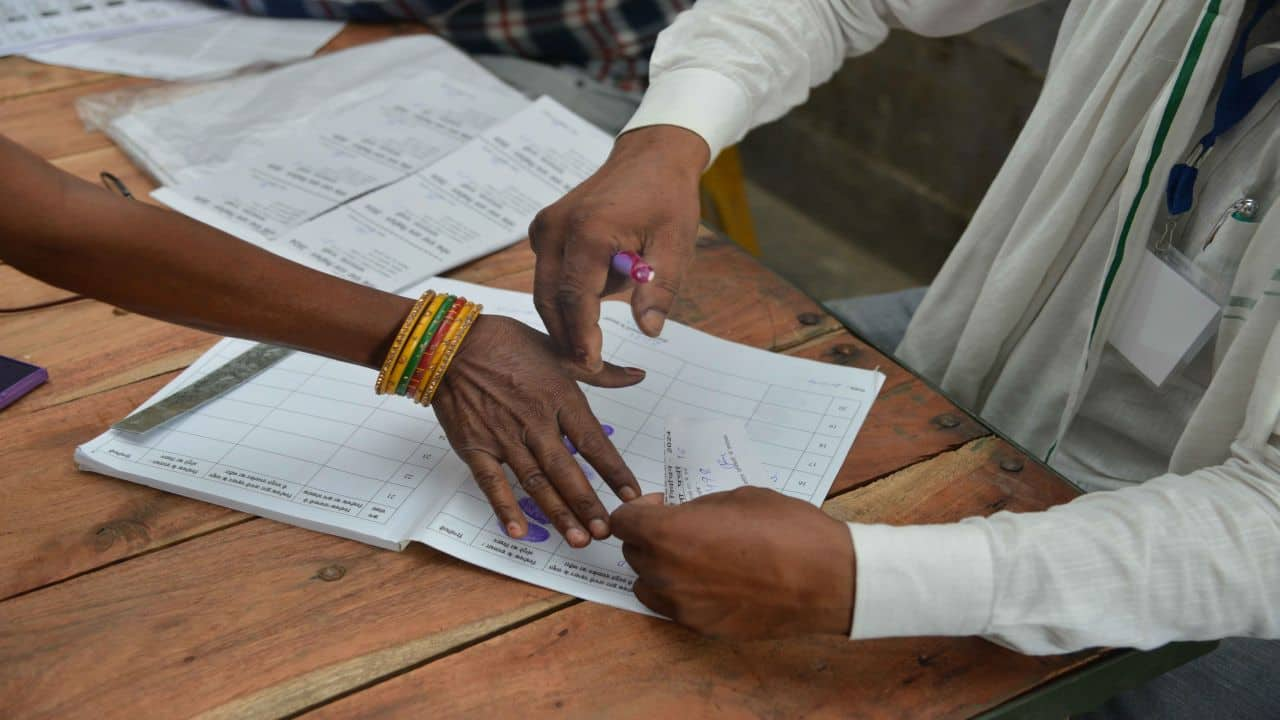

Traditionally, the EC relied on a self-declaration system—a statement from the head of a household—to enroll or retain voters during roll revisions. Officers recorded details without demanding proof of citizenship. The onus was on any objector to prove someone was not a citizen—never on the voter themselves.

This time, however, under the SIR in Bihar, about 3 crore people who were added to the electoral rolls after 2003 must provide at least one of 11 approved documents—birth certificates, parent’s birth records, land documents, etc.—to confirm their birth details and citizenship. Even existing voters not on the 2003 list must now prove they weren’t “guilty until proven innocent”, marking a reversal of previous methodology.

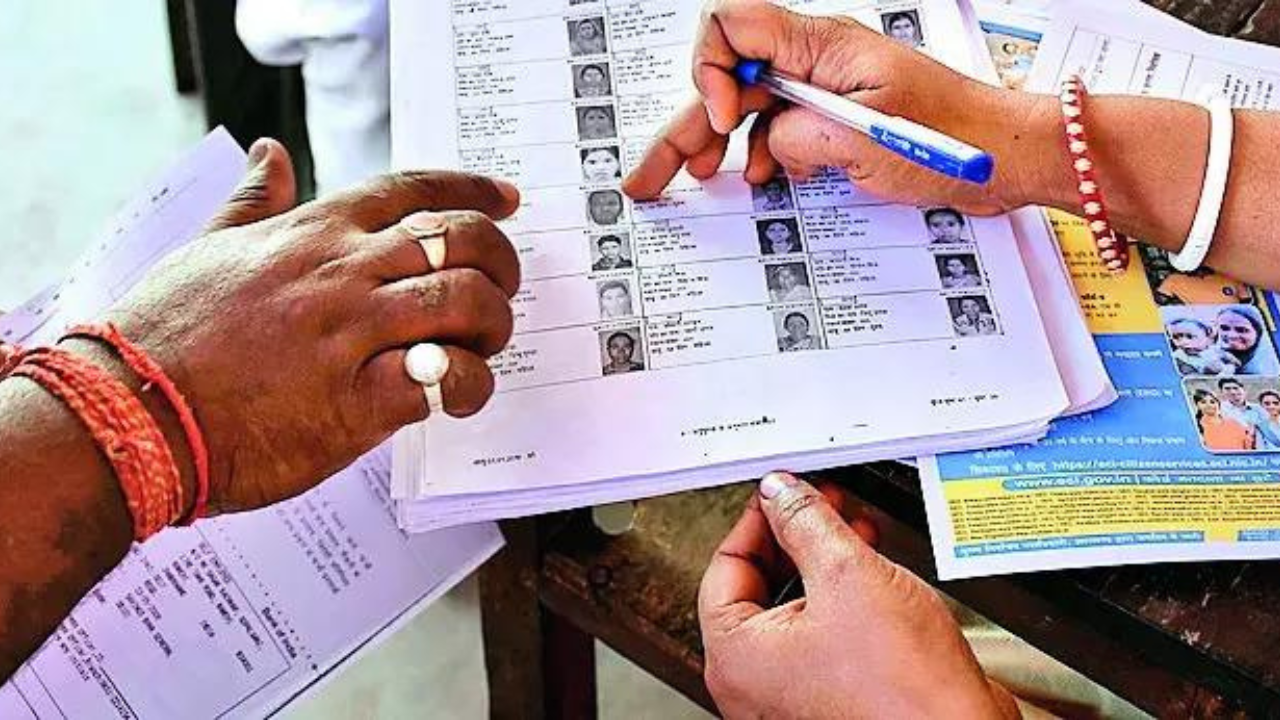

Moreover, the EC has uploaded the 2003 Bihar voter list, covering approximately 60% of the electorate, allowing this group to bypass document submission.

Why Is This Happening?

Officials say the SIR process aims to create a “robust database” by collecting documentary evidence, ensuring only citizens over 18 are included. They argue mass changes have occurred since 2003 due to migration, deaths, duplications, and suspected non-citizens. Similar rolls are being considered elsewhere in the country.

One Senior EC official told Indian Express that inconsistent documentation among new registrants since 2003 necessitated special scrutiny and proof.

Concerns & Opposition

Critics argue the new rules are unfair and risky, especially for the disadvantaged. They claim placing the burden of proof may disenfranchise poor, elderly, migrant workers, and marginalized citizens—many lacking birth or parentage documents.

Tejashwi Yadav and INDIA bloc parties warn this could exclude up to 2 crore voters, including migrants and marginalized groups. RJD MP Manoj Jha has challenged the exercise in the Supreme Court, calling it "systematic exclusion" of mobile workers.

Experts like psephologist Sanjay Kumar describe the 30-day timeframe during monsoon as a "logistical nightmare" and warn using documents like Aadhaar or MNREGA as proof would mitigate most issues. He highlights the challenge in Bihar’s literacy and documentation levels, noting only 14.7% of adults have passed 10th grade, and official birth registration rates were under 25% in 2007.

Field officers report some villages may have as few as 2% of residents able to provide proof. Pancit registers, seat-level family records, may offer relief, but uncertainty remains.

EC’s Defense

EC defends the process as constitutional (citing Article 326), legal (under Representation of the People Act), and necessary for clean, accurate rolls .

It notes SIR is permitted “at any time for reasons recorded in writing” and says door-to-door verification, recruitment of 1 lakh Booth Level Officers (BLOs) and 4 lakh volunteers, and uploading older rolls helps ensure no eligible voter is excluded.

EC claims that out of 1,000 people per polling booth, approximately 700–800 are from 2003 list and thus allowed automatic retention. Challenges are expected from the remaining few dozen per booth.

Officials stress citizens can first submit forms, documents later, reducing immediate exclusion risk .

Looking Ahead

A Supreme Court hearing on July 10 will scrutinize SIR’s timing, scope, and fairness .

Political pressure is intense: Opposition parties are marching in Patna, holding rallies, promising legal and political resistance. ECI chief Gyanesh Kumar assures citizens won't be left out, but whether the timeline is practical remains debated .

Outcomes in Bihar could shape how the EC approaches roll revisions nationally.

This development reflects the EC’s push for electoral integrity—aiming to verify citizenship, eliminate ghost voters, and modernize voter data.

Yet, it underscores real equity issues—many Bihar residents lack documents; narrow timelines raise disenfranchisement risks. Opposition voices fear this may exclude significant segments, while experts question execution feasibility.

The situation highlights a deeper question: Should the system's trust rest on self-declaration with protections, or on formal paperwork, even if challenging? Perhaps a middle-ground approach—accepting alternative proofs like Aadhaar, voter IDs, or post-declaration paperwork—could balance fairness and accuracy.

What Citizens Should Know

-

If you were on the 2003 electoral roll, you likely don’t need additional proof—just submit the 2003 extract.

-

Others must provide at least one approved document: birth certificate, school record, parent’s records, or family register.

-

Forms can be submitted first, with documents followed up later.

-

If you miss the deadline or lack papers, legal recourse is expected, including court reviews.

-

Stay informed via official EC updates and News outlets; contact your nearest BLO or election office early.

FInal Thoughts

The EC’s shift in Bihar—to burden voters with proof and reduce precious trust in existing rolls—marks a major change from past practice. Aimed at cleaner elections and citizenship validation, it faces concerns over execution, equity, and timing. Its outcome—both in the courts and at the ballot box—could influence India’s future electoral methods, including upcoming elections in other states.

With inputs from agencies

Image Source: Multiple agencies

© Copyright 2025. All Rights Reserved Powered by Vygr Media.