Bengali Speaking People and the Long Shadow of “Illegal Immigrant” Politics

For decades, Bengali-speaking people (pre-dominantly the migrant working classes) in India have lived under the shadow of suspicion, frequently accused of being “illegal Bangladeshi immigrants” regardless of their citizenship status. The controversy currently before the Supreme Court fits into a longer and troubling history of detentions, deportation attempts, and contested identities along India’s eastern frontier. Perhaps the most visible episode came in Assam in 2019, when the state published its final National Register of Citizens (NRC). The exercise was intended to identify undocumented migrants but instead left nearly two million residents off the list. Many of those excluded were poor, rural, and Bengali-speaking Muslims who had lived in India for generations. Despite holding documents such as ration cards, voter IDs, and land records, they found themselves at risk of detention or statelessness. To this day, thousands of these cases remain tied up in appeals and legal challenges.

Those declared foreigners are often sent to detention centres, particularly in Assam, where facilities have been criticised for overcrowding and inhumane conditions. Human rights groups have documented cases in which Indian citizens were mistakenly classified as foreigners and confined for years. Deportation has proved more complicated: Bangladesh frequently refuses to accept individuals unless their nationality is conclusively established. Yet reports of “pushbacks” across the border have surfaced, with testimonies alleging that Border Security Force personnel have forced groups of Bengali speakers into Bangladesh, sometimes under threat of violence. The problem is not confined to Assam. Across several states, from Delhi to Gujarat, accusations of being Bangladeshi have become a political weapon. In practice, the act of speaking Bengali is often enough to draw suspicion. Migrant workers from West Bengal, who travel widely in search of employment in construction, textiles, and domestic work, have become especially vulnerable. Many live under the constant fear of arbitrary detention or sudden deportation, their identities questioned despite their legal right to reside in the country. In this sense, the current allegations before the Supreme Court are not isolated. They are part of a larger, long-running pattern in which migration, language, and religion are entangled with questions of national security, often to the detriment of marginalised communities.

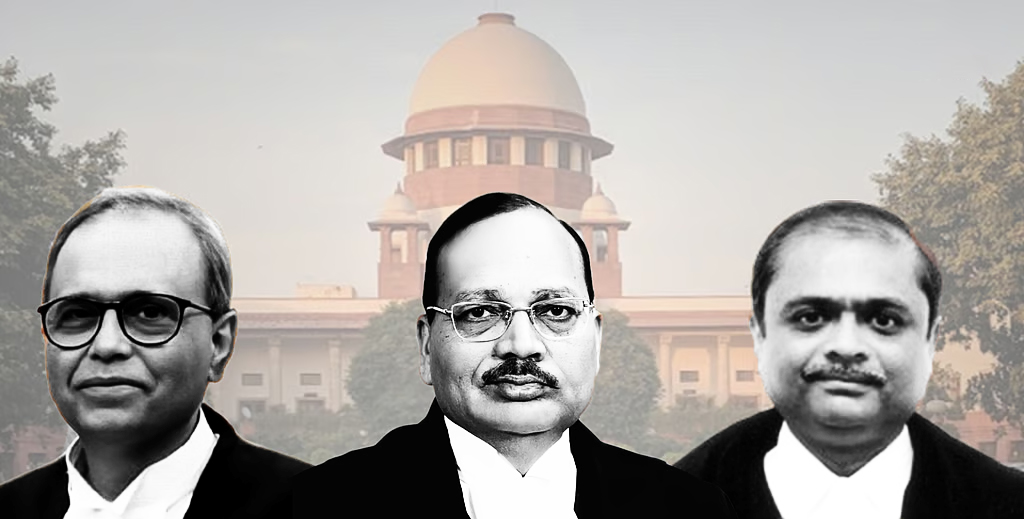

Supreme Court Questions Centre on Alleged Illegal Detention of Bengali Muslim Migrant Workers

The Supreme Court on Friday directed the Union government to respond to serious allegations that migrant Muslim workers from West Bengal were being detained unlawfully across several Indian states on suspicion of being illegal Bangladeshi nationals. A bench comprising Justices Surya Kant, Joymalya Bagchi, and Vipul Pancholi emphasised that while concerns over illegal immigration were valid, there could be no presumption of foreignness purely on the basis of language or community. “Is language a presumption of being a foreigner?” the judges asked, reflecting unease over reports that Bengali speakers were being singled out.

Case Background: From Birbhum to Bangladesh

The issue came before the apex court following disturbing reports carried by The Telegraph. According to the account, Danish Sheikh (26) and his wife, Sonali Khatun (24), both migrant workers from Birbhum district in West Bengal, were allegedly deported by Delhi Police along with their five-year-old son Sabir and three other Bengali labourers.

The case took a further turn when Sonali – referred to in court filings as “Sunali Bibi” – was reportedly arrested by Bangladeshi authorities, who themselves described her as an Indian national. A habeas corpus petition seeking her production, along with that of five others, is currently pending before the Calcutta High Court. On Friday, the Supreme Court clarified that the high court was free to hear the habeas corpus plea without waiting for its own proceedings to conclude.

Petition and Allegations

The petition before the top court was filed by the West Bengal Migrant Workers Welfare Board, represented by advocate Prashant Bhushan. He argued that Bengali-speaking Muslims were being forcibly expelled without due process, in clear violation of both Indian law and international conventions. Bhushan told the bench that in some instances, the Border Security Force (BSF) had allegedly threatened deportees with violence. “The BSF personnel threatened to shoot unless they ran to the other side,” he claimed, adding that such expulsions were being carried out without any tribunal determining nationality. He further submitted that nearly 1,000 Bengali-speaking individuals were currently detained in Gujarat alone, raising alarm over the scale of the practice.

States Under Scrutiny

The matter has wide geographical scope. Notices have already been issued to nine states — West Bengal, Odisha, Rajasthan, Maharashtra, Delhi, Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, and Haryana. On Friday, Gujarat was impleaded as well. The allegations suggest that workers migrating within India for livelihood are being harassed, detained, or deported purely on suspicion of being “illegal immigrants” from Bangladesh, a charge often levelled against poor Bengali-speaking Muslims.

Centre’s Response and Judicial Observations

Solicitor-General Tushar Mehta, appearing for the Union government, questioned the petition’s maintainability. He argued that associations or welfare boards could not claim standing in such matters. “Why have organisations come here? Let an individual appear before us saying ‘I am being pushed out.’ The moment they come, they will have to justify their presence legally,” he submitted.

Justice Kant partly agreed, acknowledging that unauthorised migration into India was indeed a problem. “There are persons who are trying to enter. In forcing them back, there should not be any difficulty. But those who are presumed to have entered, the first question is they have to show proof of citizenship,” he observed.

Justice Bagchi, however, struck a more cautious note. “There are questions of national security, integrity of the nation, and preservation of resources,” he said. “But at the same time, we have a legacy of common heritage. In Bengal and Punjab, the language is the same, the border divides us. We want the Union of India to clarify on the issue.”

Broader Implications

The controversy highlights the fraught nature of identity politics along India’s eastern border. Language and religion have often been conflated with nationality, making Bengali-speaking Muslims especially vulnerable to suspicion. The fallout of the National Register of Citizens (NRC) exercise in Assam, which left nearly two million people facing uncertainty over their citizenship status, looms large in the background. By questioning whether “language” can serve as the sole presumption of foreignness, the Supreme Court has signalled concern over discriminatory enforcement practices. Yet its simultaneous acknowledgement of “national security” and “illegal immigration” underscores the tension between civil liberties and state control at India’s borders.

Mamata Banerjee Welcomes Order

Reacting to the court’s intervention, West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee expressed relief on behalf of affected workers. In a post on X (formerly Twitter), she wrote that the Supreme Court’s directive allowing the Calcutta High Court to prioritise the habeas corpus plea came as “a huge relief to the detained workers.”

“We repose full faith in the judiciary to ensure dignity, fairness, and constitutional justice for every worker from Bengal,” she added.

What Next?

The Supreme Court has scheduled the matter for further hearing on 11 September. In the meantime, the Calcutta High Court has been asked to proceed with pending petitions, ensuring that individual cases like that of Sonali Khatun are not delayed by procedural overlaps. Whether the Centre’s eventual reply will clarify the extent of detentions – and address the allegation that Bengali speakers are being disproportionately targeted – remains to be seen. For now, the court’s pointed question resonates across India’s migrant communities: can the mere act of speaking Bengali be treated as evidence of foreignness?

With inputs from agencies

Image Source: Multiple agencies

© Copyright 2025. All Rights Reserved. Powered by Vygr Media.