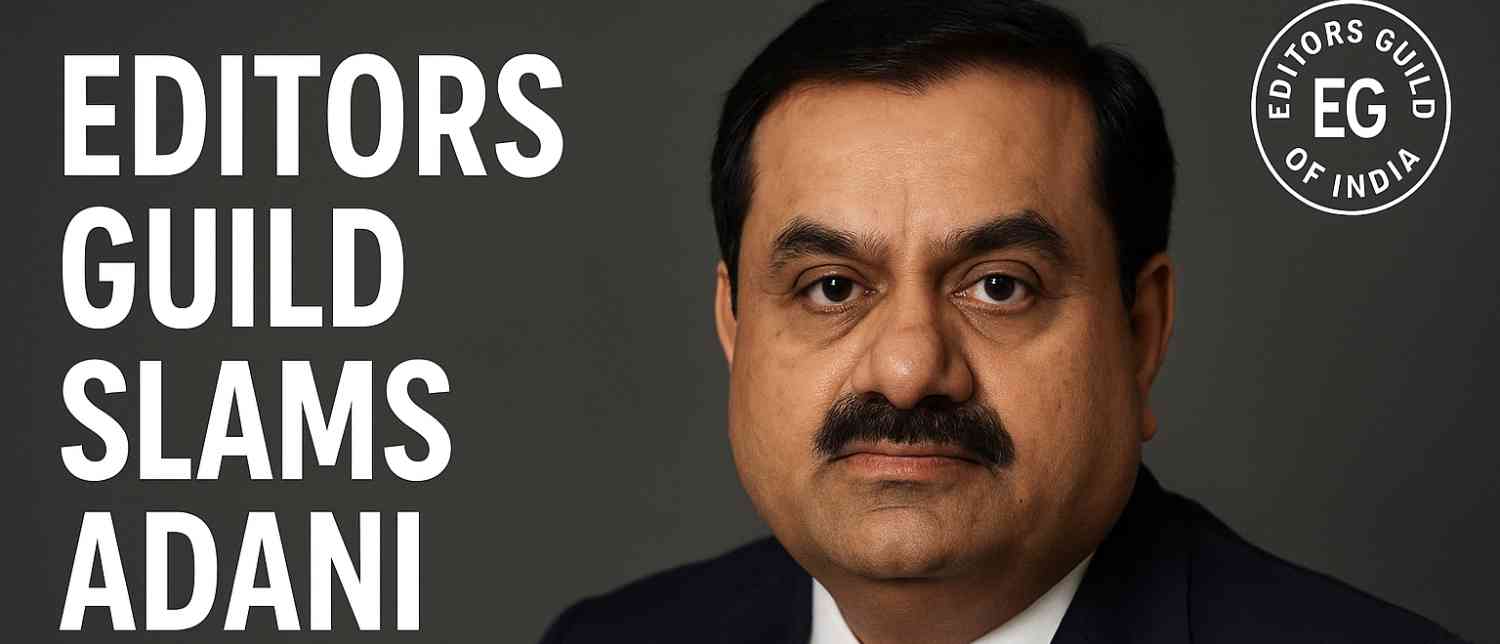

A recent Delhi court directive has sparked a major debate over press freedom and corporate influence in India. Several journalists, activists, and digital creators have confirmed that they were served notices from YouTube and the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting (I&B) to take down content deemed “unverified and ex facie defamatory” against Adani Enterprises Limited (AEL).

The Editors Guild of India has described the development as “troubling,” warning that such sweeping orders risk enabling censorship and undermining the role of a free press in democracy.

Editors Guild Expresses ‘Deep Concern’

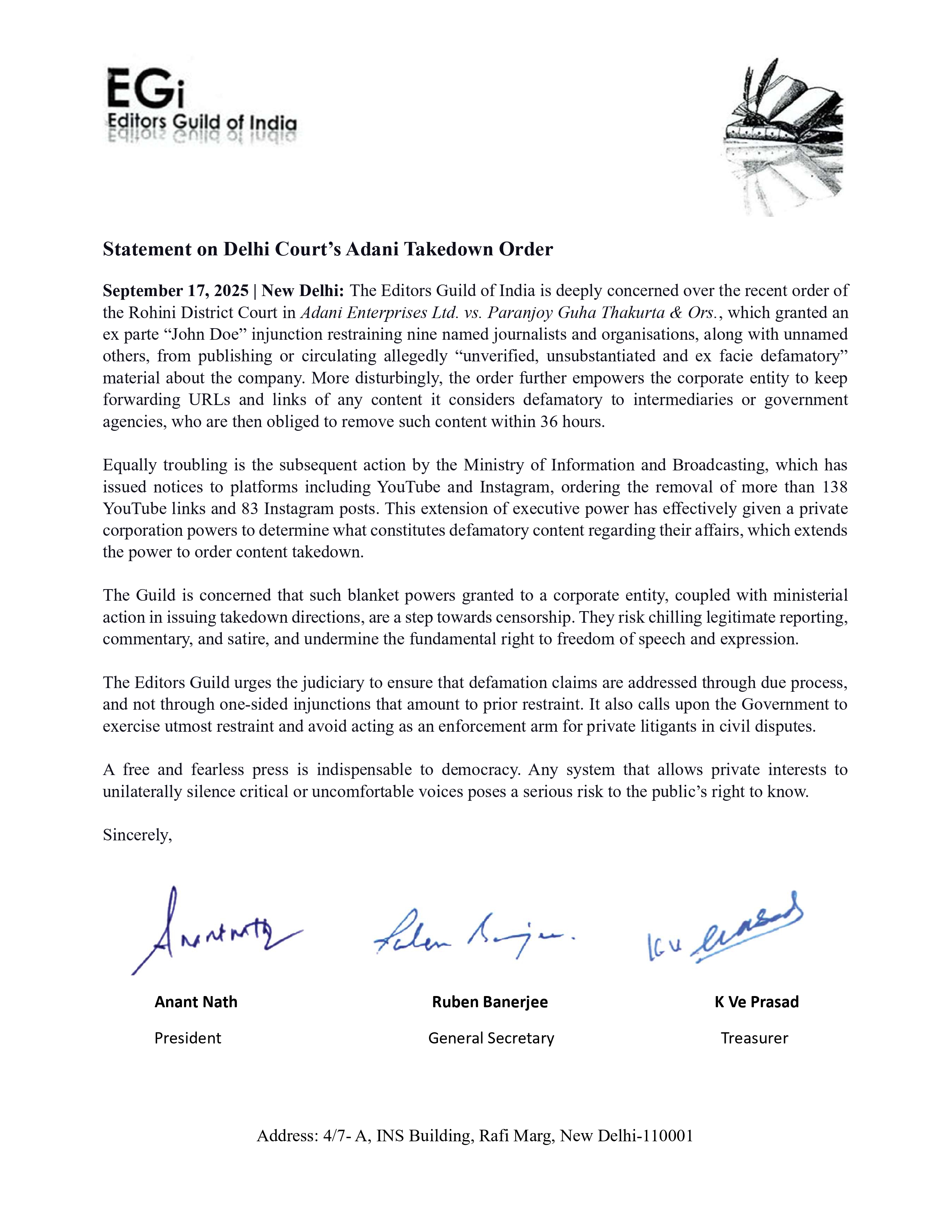

In an official statement, the Editors Guild of India voiced “deep concern” over the Delhi court’s directive. The order restrained nine journalists, activists, and organisations from publishing or circulating “unverified, unsubstantiated and ex facie defamatory” reports about AEL. It also directed the removal of all such content within five days.

The Guild highlighted an even more alarming aspect of the order:

“More disturbingly, the order further empowers the corporate entity to keep forwarding URLs and links of any content it considers defamatory to intermediaries or government agencies, who are then obliged to remove such content within 36 hours,” it said.

Calling this provision a significant overreach, the Guild also criticised the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting for issuing takedown notices to digital platforms like YouTube and Instagram. These platforms were directed to remove over 138 links and 83 posts, respectively.

According to the Guild:

“This extension of executive power has effectively given a private corporation powers to determine what constitutes defamatory content regarding their affairs, which extends the power to order content takedown.”

The Guild emphasised that granting such powers to a corporate entity, combined with ministerial enforcement, risks creating a censorship regime.

“A free and fearless press is indispensable to democracy. Any system that allows private interests to unilaterally silence critical or uncomfortable voices poses a serious risk to the public's right to know,” it added.

Creators Speak Out: ‘No Chance to Contest’

Independent creators have also raised concerns about the fairness of the process. Satirist Akash Banerjee, who runs the popular YouTube channel Deshbhakt, revealed that he and other content creators were given just 36 hours to remove more than 200 pieces of content.

“We were given no opportunity to contest the order,” Banerjee said, highlighting the lack of due process in the takedown directives.

Delhi Court Proceedings: Questions Over Defamation Claims

The controversy intensified when a Delhi district court heard challenges to the gag order. On Thursday, District Judge Sunil Chaudhary of the Rohini Court reserved his verdict after hearing arguments from both sides in a case involving journalist Paranjoy Guha Thakurta.

The Adani Group had alleged that coordinated “defamatory” content was being circulated to damage its reputation and global operations. However, the court appeared skeptical.

Judge Chaudhary remarked:

“What is the relief being asked by you? You’re not yourself sure if it’s defamatory…you’re seeking a declaration from the court. How can [an] injunction be granted if it hasn’t been declared defamatory?”

This observation was made in response to Adani Enterprises’ claims, which were based on an ex-parte interim order passed on September 6 by a Senior Civil Judge.

Defense Arguments: Who Decides What’s Defamatory?

Appearing for Guha Thakurta, senior advocate Trideep Pais argued that the September 6 order gave Adani Enterprises undue power to demand removal of content it subjectively deemed defamatory.

“The urgency is that intermediaries have been asked to remove multiple articles. Who will determine what will be defamatory has been left to the plaintiff (AEL). That’s my problem with this order,” Pais said.

He further noted:

“It has nowhere been stated how the material is defamatory. There is no reasoning as to how a prima facie case was made out… These companies have 300 media managing units. Today, the plaintiff can write to Google saying please remove this.”

Judge Chaudhary also pressed Adani’s counsel on specifics, asking:

“If you have been defamed, you should specify the quantum of damages. Here, you are only asking the court for a declaration.”

The judge questioned what exactly in Guha Thakurta’s reporting was defamatory.

Adani’s Stand: Damage to Reputation

Representing AEL, senior advocate Anurag Ahluwalia cited an article that compared Gautam Adani’s relationship with Prime Minister Narendra Modi to Elon Musk’s ties with former US President Donald Trump. The article alleged that Modi promoted Adani abroad at India’s expense and that rules were bent in the company’s favour.

Ahluwalia argued that repeated publications of such content damaged the company’s reputation:

“Should I wait for the shares to fall?” he asked, insisting that fair journalism requires backing claims with evidence.

Judge Chaudhary, however, was unconvinced, pointing out:

“The article is only saying you are friends with the PM,” and questioned whether AEL’s share prices had actually fallen because of such posts.

Parallel Appeals: Four Journalists Challenge Restraints

In another case, a Delhi court granted relief to four journalists — Ravi Nair, Abir Dasgupta, Ayaskanta Das, and Ayush Joshi — who had challenged the September 6 gag order.

Civil Judge’s order had directed them to take down previously published content, but District Judge Ashish Aggarwal ruled that the order violated basic legal principles.

Advocate Vrinda Grover, appearing for the four journalists, argued:

“Most of the challenged publications had been in the public domain since June 2024. There were no urgent circumstances justifying the civil court granting the extraordinary and exceptional relief of an ex-parte interim injunction several months after the publications.”

Grover strongly opposed sweeping orders restricting press freedom:

“It is a john doe order, in rem, order in future. Is there any law in this country which can ask anyone, particularly the press, that you won’t write or question any entity in this country? That is not what the law allows. Please note freedom of speech of expression, the journalists are agents of the press who take this right forward.”

Judge Aggarwal agreed that the lower court’s order was unsustainable, observing that the defendants were not given an opportunity to be heard and that provisions of the Civil Procedure Code (CPC) were not followed.

“The impugned order is not sustainable. I allow the appeal and set aside the impugned order without any finding on the merits of the case,” Judge Aggarwal said, remanding the matter to the lower court for reconsideration after hearing both sides.

Government’s Enforcement: 138 YouTube Videos and 83 Instagram Posts Removed

Meanwhile, the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting enforced the September 6 court order by directing platforms to remove 138 YouTube videos and 83 Instagram posts related to the Adani Group. The content removal order covered prominent journalists like Paranjoy Guha Thakurta, Ravish Kumar, and platforms such as Newslaundry and The Wire.

The ministry issued an ultimatum demanding compliance within 36 hours under the IT (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021.

Concerns Over Press Freedom and Corporate Influence

The takedown orders have triggered widespread debate about the balance between protecting reputations and safeguarding press freedom. Critics argue that by allowing ex-parte orders without hearing affected parties, the judiciary and government risk empowering corporations to silence dissenting voices and public-interest journalism.

The Editors Guild summarised the broader danger:

“A free and fearless press is indispensable to democracy. Any system that allows private interests to unilaterally silence critical or uncomfortable voices poses a serious risk to the public’s right to know.”

Final Thoughts

The Adani Enterprises defamation case, combined with the government-backed takedown of online content, has become a flashpoint in India’s ongoing debate about free speech, media freedom, and corporate accountability. While courts continue to deliberate on the legality of the gag orders, the episode underscores a pressing question: Should private corporations and the state have the power to decide what constitutes defamation before a full judicial review?

As journalists, creators, and media organisations await clarity, the outcome of these cases may set a precedent for the future of free expression and digital media regulation in India.

With inputs from agencies

Image Source: Multiple agencies

© Copyright 2025. All Rights Reserved. Powered by Vygr Media.