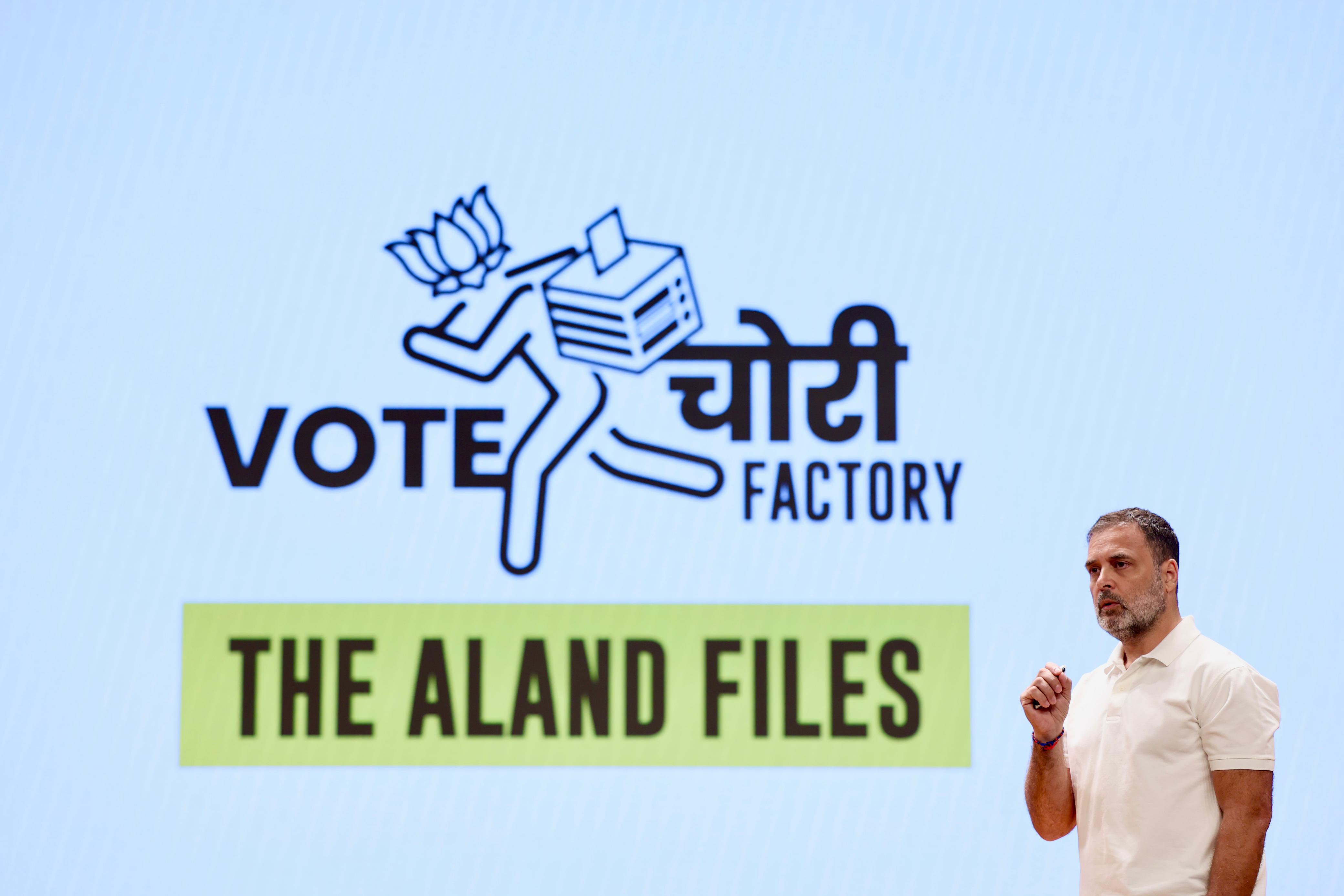

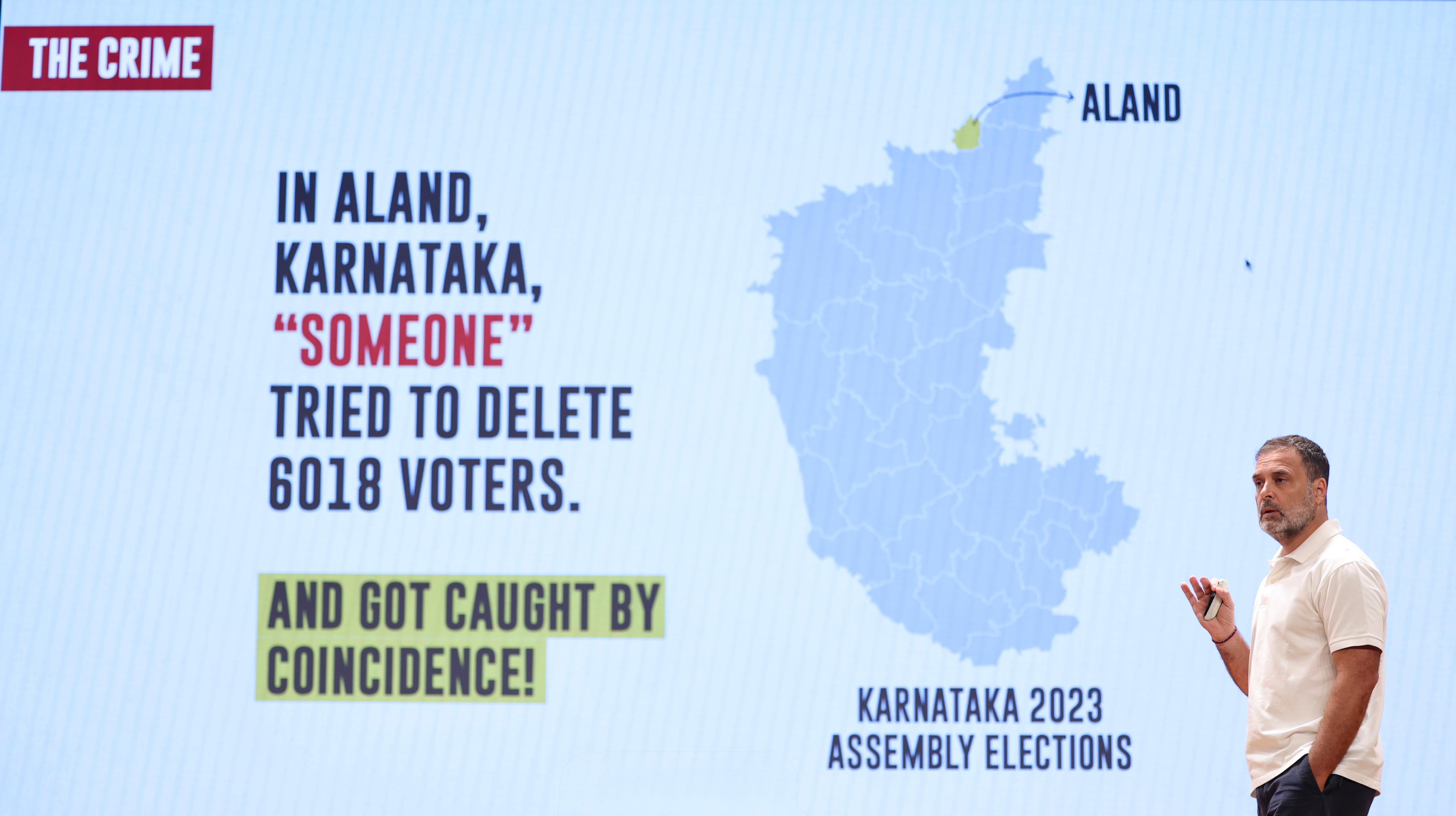

On September 18, 2025, Congress leader Rahul Gandhi made a serious allegation about large-scale voter deletions in Karnataka’s Aland constituency. He claimed that more than 6,000 votes were deleted using impersonation, software automation, and mobile phone numbers from outside the state. Gandhi said this was not an isolated event but part of a much larger, centrally coordinated operation to tamper with elections in India. The issue, according to him, raises questions about the very survival of India’s democracy.

The controversy first came to light almost by accident. A booth-level officer in Aland noticed that her uncle’s vote had vanished from the voter list. When she checked, she discovered that the application to delete her uncle’s vote had been filed in the name of her own neighbor. But the neighbor himself had no idea that his name was linked to the deletion. Neither the supposed applicant nor the voter whose name was removed had played any role in the process. This suggested that an outside force had hijacked the system.

From there, the scale of the problem became clearer. According to Gandhi, 6,018 applications were filed for voter deletions in Aland alone, impersonating actual voters. These were not genuine applications but generated using software programs and fake logins. Most of the mobile numbers linked to these deletions were traced back to states outside Karnataka, raising suspicions of a coordinated fraud. Moreover, Gandhi claimed these operations specifically targeted booths where Congress was performing well, suggesting a deliberate political motive rather than random chance.

To show how the system was manipulated, Gandhi gave the example of a woman named Godabai. He alleged that someone created a fake login in her name and attempted to delete 12 voters linked to her booth. The attempt was stopped midway, but Godabai herself had no knowledge of what was being done in her name. In this case, too, the mobile numbers involved were from outside Karnataka. Gandhi then posed critical questions that remain unanswered: Whose numbers were these? Who was operating them? From where were they operated? Who generated the one-time passwords that allowed such deletions to go through?

The Congress leader argued that automation was the only way such applications could be processed at the speed observed. As an example, he pointed to cases where two forms were submitted in just 36 seconds, something almost impossible through human effort. In another suspicious case, an individual supposedly filed forms at 4:07 a.m.—an unusual time for such activity. The pattern suggested that an automatic program was running the operation. In fact, the software appeared to be structured to pick the “first name in every booth list” and then target that name for deletion. Such systematised patterns strongly indicated mass automation.

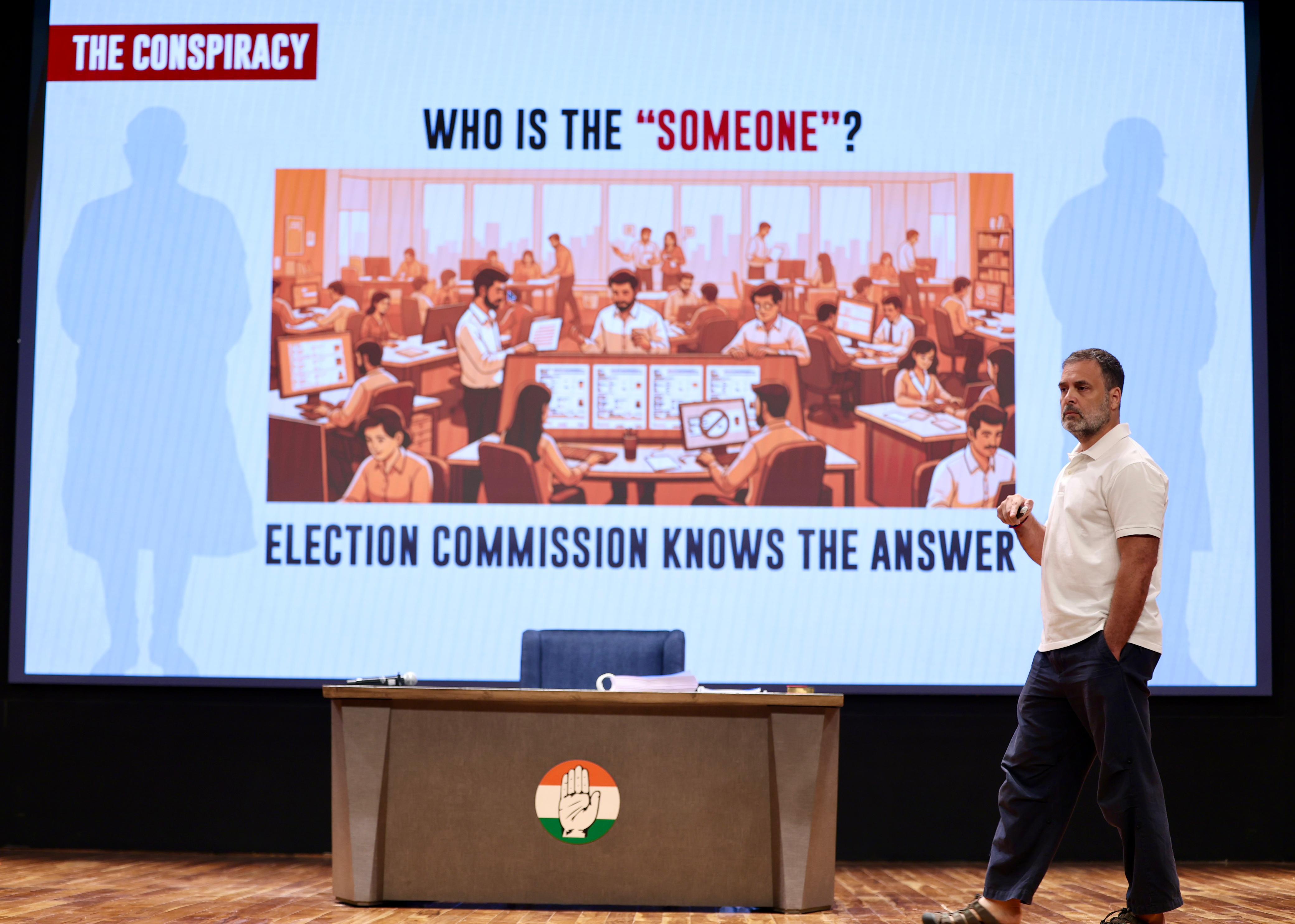

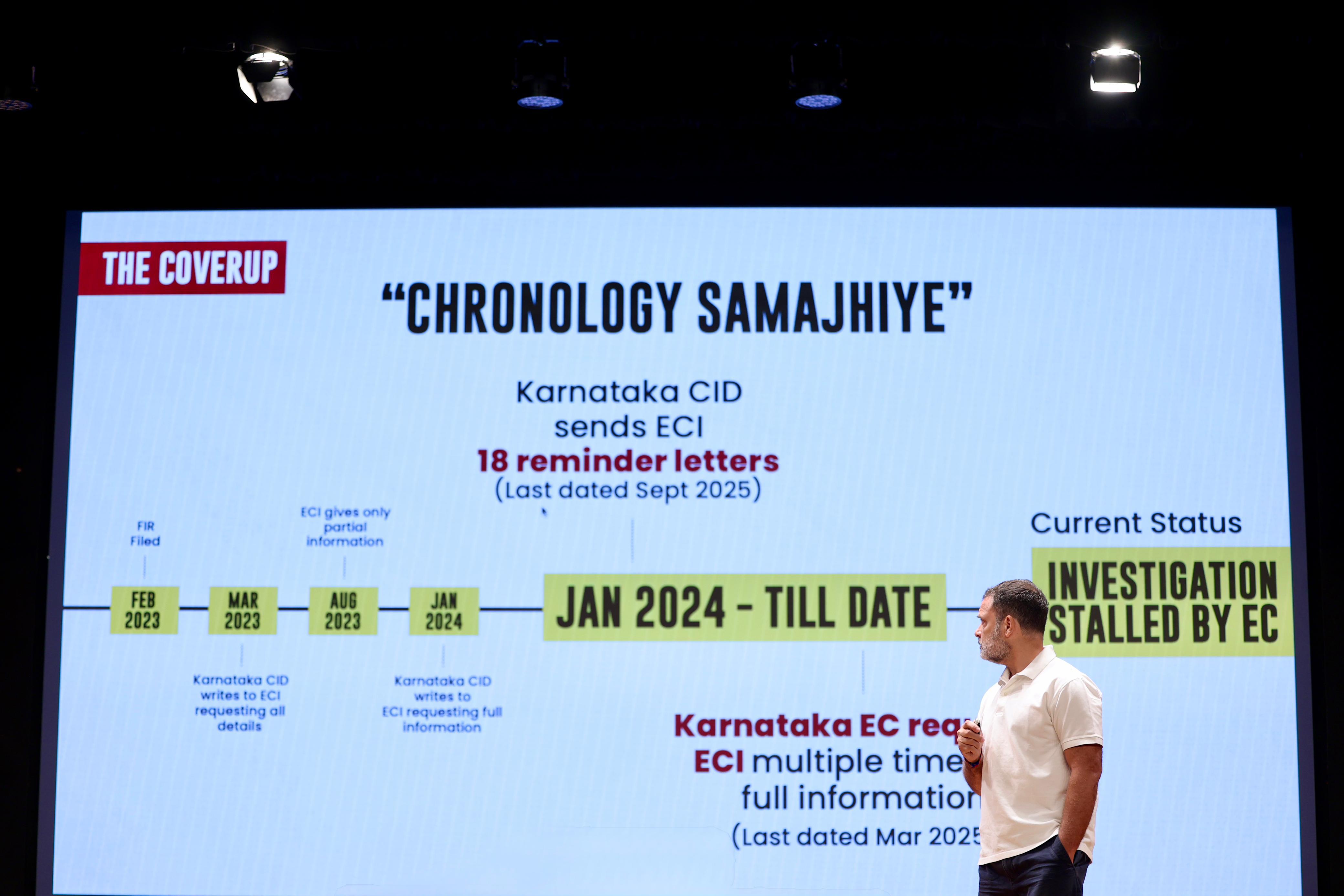

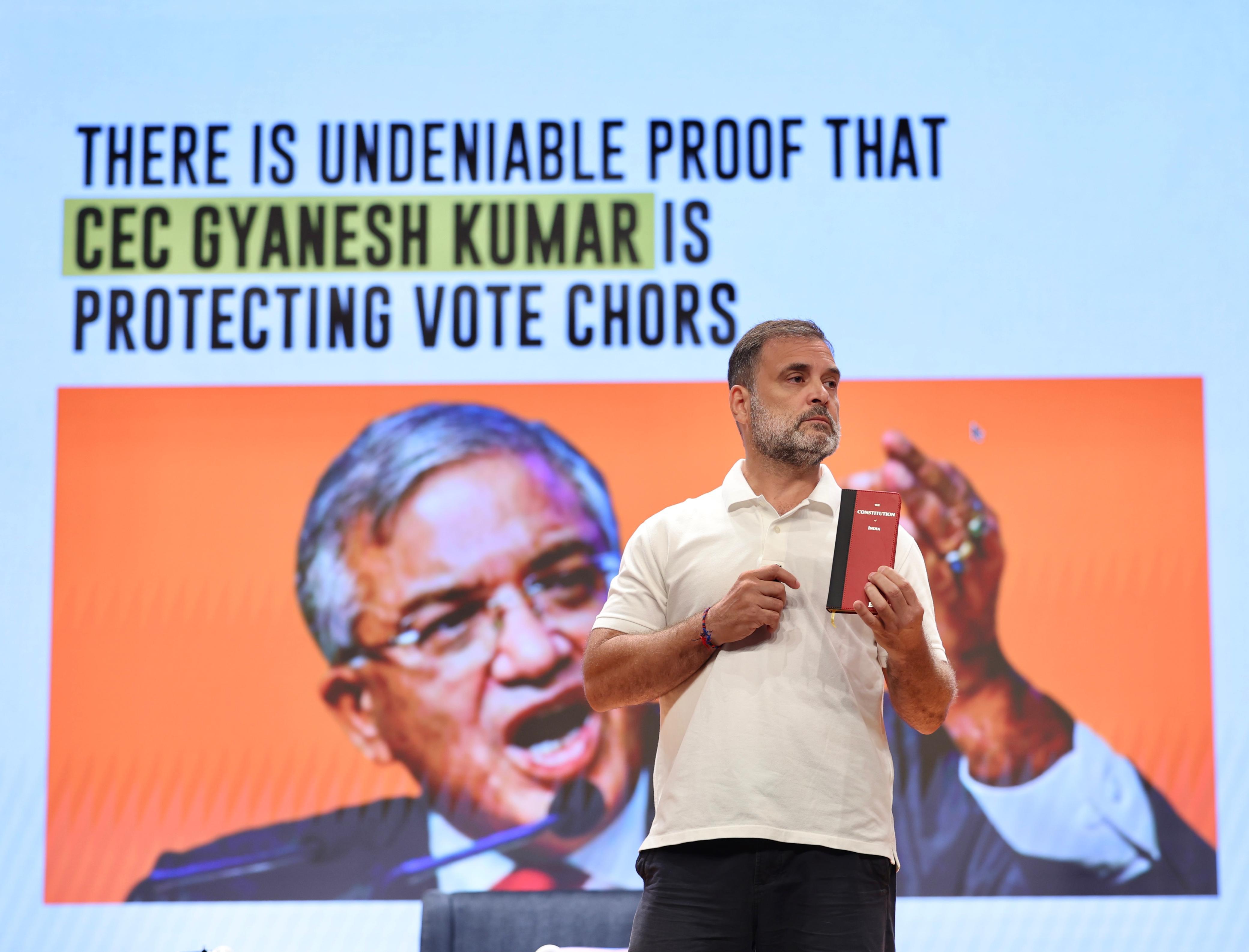

Importantly, Gandhi stressed that this was not a case of isolated mischief by local level party workers. Instead, he claimed it was a centralized operation, possibly run like a call-centre with software tools. This scale, according to him, could not have been achieved without coordination and external support. He directly accused the Election Commission of India, particularly Election Commissioner Gyanesh Kumar, of protecting those behind this manipulation. While the Aland case exposed 6,018 deletions, Gandhi suggested the actual number of deleted votes across Karnataka may be much higher, since only one suspicious batch was caught.

“This is black and white proof,” he declared. “India’s democracy is being destroyed before our eyes, and the Election Commission is shielding the culprits.”

The larger concern raised by the Congress leader is about trust in India’s electoral system. In the past, malpractice allegations mostly revolved around booth capturing or money distribution. What makes this new form more dangerous, Gandhi argued, is that it uses technology to invisibly alter voter lists. It ensures that many people may never even know their vote was deleted until election day, when they discover their name missing from the rolls.

For Gandhi, the larger message is directed to the youth of the country. He urged young people to notice how even before they cast their vote, their right is being erased by forces using advanced software and fake applications. He challenged them to try filling out two voter forms in 36 seconds to see for themselves how impossible it is without automation.

The scandal throws up a series of uncomfortable questions for Indian democracy. Who is truly behind the fake logins? Who provided the out-of-state mobile phone numbers? How were the OTPs validated for each deletion? If 6,018 deletions were exposed in one constituency by coincidence, how many thousands more across the country went unnoticed? Most importantly, what action has the Election Commission taken upon discovering such irregularities?

India’s credibility as the world’s largest democracy depends on fairness in its elections. If citizens believe their names can be quietly struck off the rolls without their knowledge, confidence in the system shrinks. Gandhi warned that this is not merely about one seat in Karnataka but about the basic foundation of how India votes. The chilling detail in his presentation was that the fraud was not stopped by institutional safeguards but caught purely by chance—when one officer happened to look into her uncle’s missing name.

The press conference is expected to spark fierce political debate in the days to come. Congress is set to use the issue as proof of deeper electoral manipulation, while the Election Commission and ruling party will be pushed to respond. On social media, many young voters have already begun expressing concern about whether their own names could also have been deleted without their knowledge. As the issue grows, demands for greater transparency in voter roll management and stricter election safeguards are likely to increase.

At its heart, the Aland voter deletion case is not just about one constituency or one election. It is about whether Indian democracy can withstand high-tech sabotage. For Rahul Gandhi, the evidence in Aland is a warning signal: democracy can be rigged not just at the polling booth, but long before polling day, through invisible deletions made possible by centralised software and weak oversight.

With inputs from agencies

Image Source: Multiple agencies

© Copyright 2025. All Rights Reserved. Powered by Vygr Media.