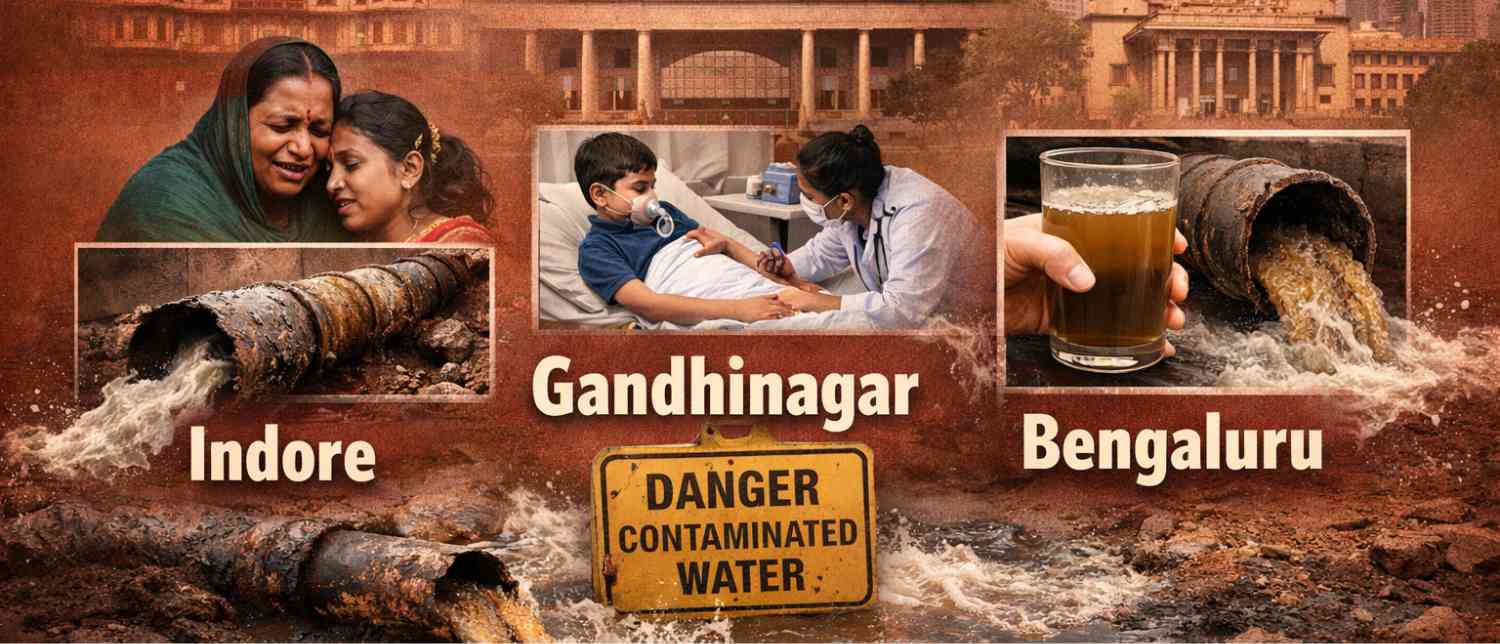

India’s most celebrated cities—those repeatedly branded as “clean,” “planned,” and “well-governed”—are today confronting a grim and deeply unsettling reality. From Indore to Gandhinagar to Bengaluru, sewage-contaminated drinking water has triggered disease outbreaks, hospitalisations, and deaths, exposing a systemic failure in urban water governance that awards, rankings, and slogans have failed to address.

The crisis first came sharply into focus in Indore, Madhya Pradesh, where at least 17 people lost their lives and more than 200 were hospitalised after drinking contaminated tap water in late December 2025 and early January 2026. Within days, similar alarms began sounding in Gandhinagar, Gujarat’s capital, and Bengaluru, India’s technology hub—suggesting that Indore was not an isolated tragedy, but part of a much larger national pattern.

Across urban India, unsafe tap water is no longer a seasonal anomaly tied to monsoons. It has become a year-round public health threat—one rooted in ageing infrastructure, poor planning, weak accountability, and a governance culture that responds only after citizens fall ill.

Indore: When India’s ‘Cleanest City’ Became Ground Zero

Indore’s reputation precedes it. Repeatedly ranked India’s cleanest city under the Swachh Survekshan, it is often held up as a model of urban success. Yet on December 31, 2025, residents of Bhagirathpura began reporting severe diarrhoeal illness after consuming tap water. By January 6, 2026, at least 17 people had died, and over 310 patients had been admitted to hospitals since December 24.

Official statements cited by the media confirmed what residents feared: damaged and leaking water pipelines had allowed sewage to enter the drinking water supply. On January 6, the Madhya Pradesh government acknowledged at least eight deaths before the High Court, underscoring the gravity of the situation.

The Indore outbreak stripped away the illusion that cleanliness rankings equate to public health safety. While Swachh Survekshan focuses heavily on visible sanitation—solid waste management, toilets, behavioural change—water infrastructure remains largely invisible, buried underground and ignored until it fails catastrophically.

Gandhinagar: Typhoid in a ‘Planned’ Capital City

Even as Indore reeled, Gandhinagar was confronting its own waterborne health emergency. In early January 2026, a sudden surge in typhoid cases was reported across multiple localities, particularly sectors 24, 26, 28, and Adiwada.

Health authorities confirmed between 70 and 85 active typhoid cases, with a total of 144 cases registered by January 7. More than 150 children were hospitalised, prompting Gandhinagar Civil Hospital to open a 30-bed paediatric ward. Young patients presented with high fever, vomiting, and gastrointestinal symptoms, though none were reported to be in critical condition.

The cause was quickly identified: contaminated drinking water. At least seven leaks were found in the city’s pipeline network, allowing sewage to mix with potable water. District officials began super chlorination to contain the outbreak, while Municipal Commissioner J.N. Vaghela stated that fresh water samples were showing improvement.

What made Gandhinagar’s case especially disturbing was the revelation that the problem was not ageing infrastructure alone. Despite a ₹257-crore 24x7 water supply project, officials admitted that new pipelines had been laid dangerously close to sewer lines. When high-pressure water began flowing, weak pipes developed cracks, creating direct pathways for contamination.

This was not a technical oversight—it was a failure of planning and public safety, raising serious questions about accountability in urban development projects.

Bengaluru: Contamination in India’s Technology Capital

In Bengaluru, residents of KSFC Layout in Lingarajapuram have been battling unsafe tap water for months. But the full extent of contamination became undeniable only in early January 2026, when households discovered foul-smelling, frothy water and thick layers of dark sewage silt while cleaning underground sumps.

At least 30 households reported diarrhoea, vomiting, and stomach infections, forcing residents to rely on private water tankers for over a week. Bengaluru Water Supply and Sewerage Board (BWSSB) officials confirmed that sewage had entered the potable water system, though the exact breach point remained unidentified.

Residents expressed frustration over what they described as a “trial-and-error” investigation, with officials digging up multiple locations in search of leaks. Bengaluru’s situation highlights another recurring problem: fragmented governance. Multiple agencies oversee water supply, sewage, stormwater drains, and roadworks, often leading to blame-shifting and delayed repairs.

For a city that markets itself as a global technology hub with one of the highest municipal revenues in the country, the irony is stark. Many residents still boil water or depend on expensive private suppliers—a daily reminder that economic growth has not translated into basic water security.

A National Pattern: 5,500 Sick, 34 Dead in One Year

Indore, Gandhinagar, and Bengaluru are not exceptions. Between January 2025 and January 7, 2026, at least 5,500 people fell ill and 34 died across 26 cities in 22 states and Union territories after consuming sewage-contaminated piped drinking water. Sixteen of these cities were state capitals.

Diarrhoea was the most commonly reported illness, followed by typhoid, hepatitis, and prolonged fever. In nearly every case, investigations traced contamination to the same source: sewage mixing with drinking water due to leaking, corroded, or poorly laid pipelines running perilously close to sewer lines.

In just one month—between December 2025 and January 7, 2026—19 people died and over 3,500 fell ill in at least 11 reported incidents across cities including Patna, Raipur, Dehradun, Guwahati, Jammu, Ranchi, Chennai, Gurugram, and Indore.

These outbreaks cut across seasons, demolishing the long-held assumption that water contamination is primarily a monsoon problem. Sewage-contaminated tap water is now a year-round threat.

Ageing Infrastructure and Invisible Failures

A common thread runs through these crises: ageing and poorly maintained infrastructure. Many Indian cities continue to rely on water distribution networks laid more than four decades ago. In Delhi, for example, around 18 per cent of water pipes are over 30 years old, according to the Delhi Jal Board.

Cracks in these pipes—often laid alongside or below sewer lines—become contamination gateways whenever pressure drops or leaks occur. In Ranchi, officials have identified more than 300 damaged pipeline locations. In Patna’s Kankarbagh Housing Colony, residents report tap water so polluted it causes itching on contact, despite repeated complaints and temporary repairs.

Even cities with newer infrastructure are not immune, as Gandhinagar’s outbreak demonstrated. Planning without sustained maintenance and oversight is meaningless.

Governance Gaps and the Accountability Void

Legally, municipal corporations are responsible for ensuring safe drinking water, while state-level agencies design and operate bulk supply networks. Health surveillance falls under state health departments, guided by the Integrated Disease Surveillance Programme of the Union Ministry of Health and Family Welfare.

At the national level, the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs oversees urban water infrastructure through schemes like AMRUT and AMRUT 2.0, while water quality standards are set by the Bureau of Indian Standards.

Yet governance remains overwhelmingly reactive. Action is typically triggered only after hospitals report disease spikes. Investigations are announced, compensation promised, and officials transferred—but systemic reform rarely follows.

This represents not just administrative failure, but a violation of fundamental rights. The Supreme Court has interpreted Article 21 of the Constitution to include the right to clean drinking water as intrinsic to the right to life. Unsafe tap water is not an accident—it is governance failure.

Promises vs Reality: AMRUT and Urban Water Security

AMRUT 2.0, launched in October 2021, promised water-secure cities. Under the Pey Jal Survekshan, cities are assessed on water quality, quantity, and coverage. Yet government data shows that only 46 of 485 surveyed cities—less than 10 per cent—reported providing 100 per cent clean water as of February 29, 2024.

With the Economic Survey 2023–24 projecting that over 40 per cent of India’s population will live in cities by 2030, pressure on already fragile water systems will intensify.

There are success stories. Puri in Odisha’s “Drink from Tap” mission delivers round-the-clock potable water meeting national standards, backed by upgraded infrastructure, continuous monitoring, and community participation. But such examples remain rare.

The Human Cost of Unsafe Water

Water contamination hits the most vulnerable hardest—children, the elderly, and low-income families who depend entirely on municipal supply. While middle-class households may install filters or buy bottled water, poorer communities bear the brunt of illness, medical expenses, missed school days, malnutrition, and, in extreme cases, death.

These costs never appear in GDP figures or cleanliness rankings, but they steadily erode public trust and deepen inequality.

Redefining ‘Clean’ Cities

India’s urban future depends on confronting this blind spot. Clean streets and awards cannot compensate for poisoned taps. Investment must shift toward underground infrastructure—modernising pipelines, separating sewage and water networks, managing pressure, deploying sensors, and mandating third-party audits.

Water safety must be treated as a public health priority, not merely an engineering challenge. Transparency is crucial. A truly clean city would publish real-time water quality data and issue immediate alerts, much like air quality warnings.

The deaths in Indore and illnesses in Gandhinagar and Bengaluru are not anomalies—they are warnings. Until Indian cities redefine cleanliness to include safe, reliable drinking water, urban success will remain a hollow promise—one that costs lives instead of improving them.

With inputs from agencies

Image Source: Multiple agencies

© Copyright 2025. All Rights Reserved. Powered by Vygr Media.