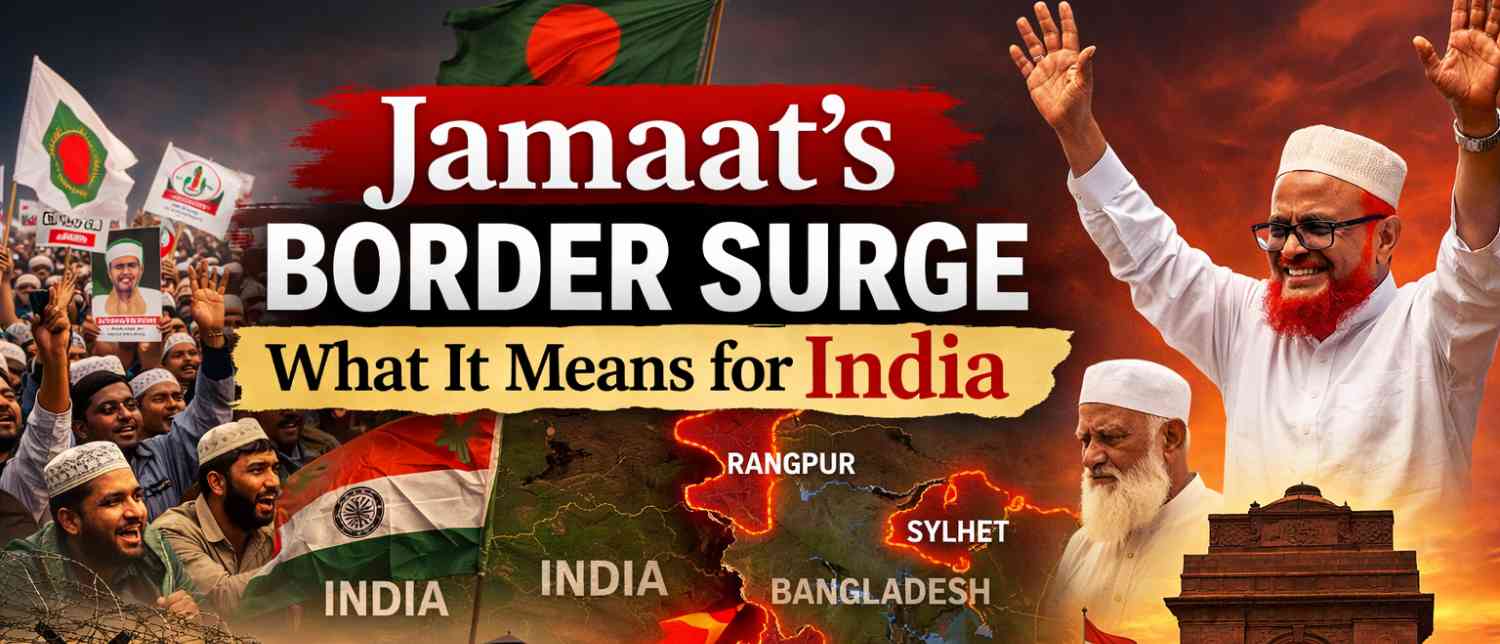

The outcome of Bangladesh’s 2026 general election has not stopped at the Radcliffe Line. It has travelled swiftly across the 4,096-kilometre frontier—the sixth-longest land boundary in the world—and settled into conversations in Dhubri, Cooch Behar, Shillong and Siliguri. In India’s Northeast and eastern borderlands, the verdict is being read not as distant politics, but as a strategic signal.

Two political messages emerged simultaneously from the 13th Jatiya Sangsad election. First, the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) secured a sweeping mandate, winning 208 of 299 seats—enough to form a decisive government. Second, and more consequential for India’s border calculus, the Bangladesh Jamaat-e-Islami (Jamaat) registered an unprecedented surge, emerging as the second-largest party with 68 seats and 31.76 percent of the vote.

This is not merely an electoral fluctuation. It is a structural shift in Bangladesh’s political demography.

From Margins to Mainstream

Jamaat’s 2026 performance marks its highest tally ever. Its previous best was in 1991, when it secured 18 seats with roughly 12 percent of the vote. In contrast, this time it contested 223 of 300 constituencies and achieved 68 victories. Even more striking is the broader right-wing Islamist vote share, which has climbed to approximately 38 percent—far beyond the historical ceiling of around 15 percent.

The context matters. Jamaat’s registration was cancelled by Bangladesh’s Supreme Court in 2013, and it could not contest elections in 2014, 2018 and 2024. Some of its leaders contested the 2018 election under the BNP symbol in a tacit understanding, but the party itself was politically marginalised for over a decade.

The transitional phase under interim leader Mohammed Yunus created space for organisational consolidation. With the Awami League barred from contesting, a political vacuum opened. Jamaat used that window to prepare electorally, expand networks and reintroduce itself to voters. The 2026 result reflects not just campaign momentum but the gradual normalisation of a once-banned party.

For India, the appropriate lens is neither alarm nor indifference. The BNP governs. Yet Jamaat’s strengthened parliamentary presence will shape policy debates, ideological narratives and street mobilisation in Bangladesh over the next five years.

The Border Geography: Where the Surge Concentrates

Geography adds a security dimension to political change. Three-quarters of Jamaat’s parliamentary seats—58 out of 68—have come from divisions bordering India.

Bangladesh’s frontier touches six divisions: Rangpur, Rajshahi, Khulna, Mymensingh, Sylhet and Chittagong. The stretches adjacent to West Bengal and Assam are considered particularly sensitive.

Jamaat’s dominance is geographically clustered:

-

Khulna Division: 25 of 36 seats; vote share 48.26 percent

-

Rangpur Division: 16 of 33 seats; vote share 39.78 percent

-

Rajshahi Division: 11 of 39 seats; vote share 39.71 percent

In Khulna, Jamaat won:

-

3 of 4 seats in Kushtia

-

All 2 seats in Meherpur and Chuadanga

-

1 of 2 in Jhenaidah

-

5 of 6 in Jessore

-

All 4 in Satkhira

In Rangpur, bordering West Bengal, Assam and Meghalaya—and lying close to Bhutan and Nepal through India’s narrow Siliguri Corridor—Jamaat captured all four seats in Nilphamari, two of three in Kurigram, and five of six in Rangpur city.

In Rajshahi, which borders West Bengal’s Malda and Murshidabad districts, it secured seven seats—four in Chapai Nawabganj and three in Rajshahi constituencies—along with one each in Joypur and Naogaon.

Yet, crucially, the BNP still dominated border areas overall, winning 124 of 160 seats in frontier divisions. Even in Khulna and Rajshahi, the BNP maintained substantial representation.

This is consolidation—not takeover.

The Northern Optics: Assam’s 263-Km Frontier

In Assam, especially along the Dhubri–Kurigram stretch marked by unfenced riverine patches, erosion-prone chars and cattle-smuggling routes, the results carry symbolic weight.

In Kurigram, Jamaat won three of four seats; the fourth went to the anti-India National Citizens Party (NCP). The BNP failed to secure any seat there. In neighbouring Gaibandha, Jamaat captured four of five seats, with the BNP narrowly winning one.

The NCP’s presence adds rhetorical heat. Its leader Hasnat Abdullah had earlier warned that if India destabilised Bangladesh, the party might support forces aiming to sever India’s “Seven Sister” states—a provocative statement widely noted in Assam.

Optics matter on sensitive frontiers. But optics are not evidence of imminent destabilisation.

Security Voices: Preparedness Without Panic

Former Assam DGP Bhaskar Mahanta describes the outcome as a political shift, not a fundamentalist takeover. A decisive BNP mandate, he argues, prevents the administrative vacuum that non-state actors often exploit.

Former SSB Special Director General Jyotirmoy Chakravarty situates Jamaat’s rise within continuity. Jamaat aligned with BNP governments since 1996, joined the cabinet in 2001 with 14 seats, saw its registration declared illegal in 2013 and restored in 2025 under conditions. This rise must be read within that arc—not through alarmist headlines.

Lt Gen Rana Pratap Kalita adds nuance. Jamaat’s strength in rural and border districts stems partly from grassroots networks and latent anti-India sentiment. Urban voters, women and youth appear to have shown relative resistance.

He warns not of immediate destabilisation, but gradual exploitation. Border populations often view fencing, surveillance and cattle seizures as disruptive. Jamaat capitalised on those grievances.

The spectre of insurgent camps—like earlier decades when ULFA operated from Bangladeshi soil—cannot be entirely dismissed, though there is no current evidence of revival.

The common thread among security assessments: vigilance, not panic.

The Historical Memory: Chittagong and 1971

Indian security agencies remember the 2004 Chittagong arms haul—ten truckloads of arms allegedly destined for ULFA. Among those convicted was Motiur Rahman Nizami, Jamaat’s Ameer and a cabinet minister in a BNP-led government. He and ULFA chief Paresh Barua (in absentia) were sentenced to life imprisonment. Nizami was later executed in 2016 after conviction by Bangladesh’s International Crimes Tribunal for his role in the 1971 Demra massacre, where 800–900 unarmed Hindu civilians were killed.

While Jamaat’s current leadership distances itself from militancy, that precedent explains why Indian agencies will closely watch border developments.

Dhaka Breakthrough: The Capital Factor

Perhaps the most underappreciated dimension of the election is Jamaat’s breakthrough in Dhaka. It secured six of 20 metropolitan seats.

Dhaka is not just another constituency cluster; it is the centre of administrative authority, media influence and ideological contestation. A foothold in the capital gives Jamaat narrative power and bargaining leverage.

As geopolitical analyst Asif bin Ali observed, this signals that Jamaat’s appeal is no longer confined to peripheral or border regions—it is entering the urban mainstream.

Why Voters Turned to Jamaat

Multiple explanations converge:

-

Repression Narrative: Professor Waresul Karim argues that Jamaat was one of the biggest targets of Awami League repression over 15–17 years. In border areas like Satkhira, homes of activists were allegedly bulldozed. Sympathy for the “oppressed” played a role.

-

Grassroots Discipline: Human rights activist Rezaur Rahman Lenin highlights Jamaat’s operational discipline and social welfare initiatives—schools, healthcare services and community infrastructure.

-

Leadership Vacuum: Voters disillusioned with mainstream parties sought alternatives.

-

Tactical Voting Distortions: Karim contends Jamaat’s real strength was historically underestimated because BNP–Jamaat tactical voting blurred distinctions.

-

Modernised Image: Alignment with student groups via the NCP lent Jamaat a “semblance of modernity.” Support for reform proposals—such as separation of powers between president and prime minister—reinforced that perception.

Karim rejects portrayals of Jamaat as inherently extremist, insisting it will not form paramilitaries or destabilise borders and would likely pursue pragmatic ties with India.

The Ideological Question

Yet ideology cannot be ignored.

Jamaat’s past includes collaboration with the Pakistani Army and support for the Rajakar militia during the 1971 Liberation War. That legacy remains politically charged.

In 2026, Jamaat moderated its tone—expressing support for minority rights and stepping back from explicit calls for a Sharia-based state. It even fielded a Hindu candidate (unsuccessfully).

However, full membership (rukon) remains constitutionally restricted to Muslims. The party fielded no women candidates. Its Ameer publicly stated that women should not occupy leadership positions, telling Al Jazeera: “Allah did not permit it.”

Bangladeshi security assessments have also noted ideological overlaps between Jamaat, its student wing Islami Chhatra Shibir, and groups like Jamaat-ul-Mujahideen Bangladesh (JMB) and Harkat-ul-Jihad al-Islami Bangladesh (HuJI-B)—allegations the party denies.

For India, the issue is operational. Any weakening of Bangladesh’s internal counter-extremism vigilance could have spillover effects.

Limits of the Surge

Importantly, Jamaat failed to win in Sylhet division, despite its proximity to Assam and Meghalaya. The BNP swept all 19 seats there; Jamaat’s ally Khelafat secured one.

In Mymensingh, Jamaat won three seats to BNP’s 15. In Chittagong, it won three while BNP captured 45.

Smaller Islamist allies made limited gains: NCP won three border seats; Khelafat Majlis one in Sylhet; Bangladesh Khelafat Majlis one in Mymensingh. Islami Andolon Bangladesh has no representation in border divisions.

The pattern is selective and regional—not a sweeping Islamist wave.

Narrative Spillover Inside India

The more proximate risk may lie not in infiltration but in narrative spillover. In Assam and parts of West Bengal, identity politics is already sensitive. Amplified rhetoric about “Islamist consolidation” could deepen suspicion within border communities.

Radicalisation today often feeds on grievance and polarised messaging, not necessarily on cross-border movement.

An atmospheric shift is more plausible than a kinetic one.

Diplomatic Signals from Dhaka

Post-election commentary from BNP adviser Humayun Kabir called for “balanced relations” with India while raising concerns about rising “Hindu extremism” in parts of Indian society. He framed radicalisation as a broader South Asian phenomenon but maintained that Bangladesh is “not at that level.”

This suggests recalibration—not rupture. The architecture of India–Bangladesh security cooperation remains intact.

What Should India Do?

-

Strategic Patience: Democratic outcomes cannot be wished away. Jamaat’s rise reflects domestic dynamics—economic anxieties, identity politics, organisational discipline.

-

Institutional Engagement: Keep security cooperation insulated from partisan swings.

-

Strengthen Border Districts: Development in West Bengal, Assam, Tripura and Meghalaya is the best long-term defence.

-

Avoid Rhetorical Overreaction: Alarmism could strengthen hardline narratives in Bangladesh.

As Chakravarty cautions, rising religious polarisation within India could inadvertently strengthen Jamaat’s anti-India narrative.

A New Phase, Not a Crisis

The 2026 election marks a new phase in Bangladesh’s political evolution. Jamaat’s leap from the margins to 68 seats, its dominance in Khulna, Rangpur and Rajshahi, its breakthrough in Dhaka and its concentration along the India frontier are significant.

Yet Bangladesh remains a plural polity. The BNP leads with 208 seats. Civil society is active. Institutions endure.

For India, this is a shift to manage—not a crisis to dramatise.

Geography ensures interdependence. Political currents in Dhaka will ripple across the border. The task for New Delhi is composure: vigilant borders, firm security, pragmatic diplomacy—and restraint in rhetoric.

The quieter the discourse, the steadier the frontier.

With inputs from agencies

Image Source: Multiple agencies

© Copyright 2025. All Rights Reserved. Powered by Vygr Media.