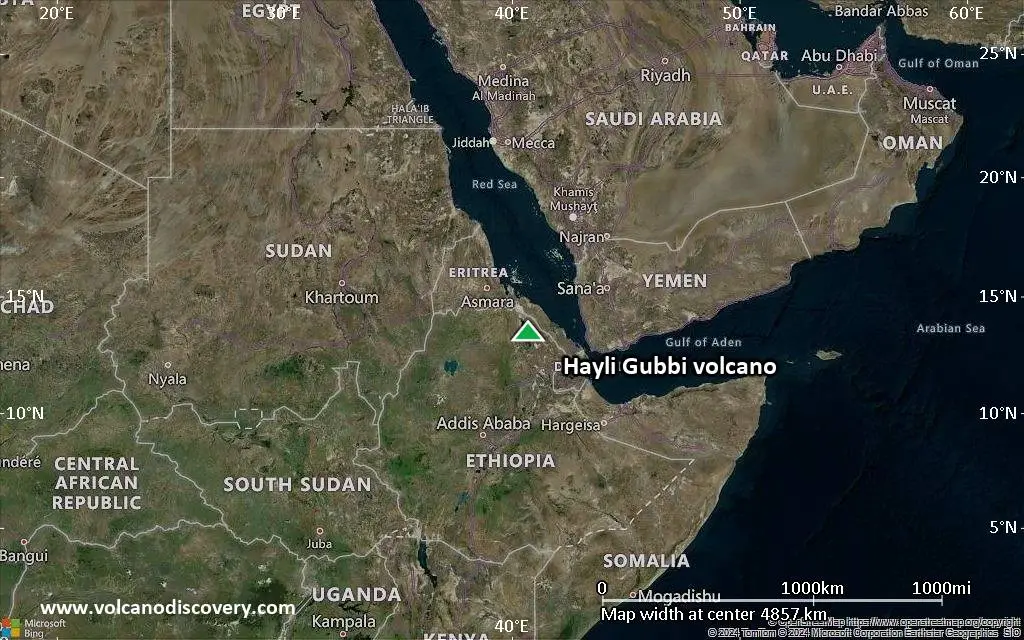

A rare geological event unfolded this week when the long-dormant Hayli Gubbi volcano in Ethiopia erupted after an astonishing 12,000 years of inactivity. What began as a massive explosive outburst in the Afar region quickly turned into an international concern, as thick plumes of volcanic ash travelled thousands of kilometres, sweeping across the Red Sea and drifting into Yemen, Oman, India, and even parts of northern Pakistan.

By Monday night, the ash cloud had already entered Indian airspace, hovering at high altitudes above Gujarat, Rajasthan, Haryana, and Delhi — prompting aviation advisories, flight cancellations, and widespread speculation about its impact on air pollution.

A Rare Eruption After 12,000 Years

On Sunday morning, November 23, the Hayli Gubbi volcano erupted dramatically, breaking a millennia-long period of dormancy. Located about 800 km northeast of Addis Ababa in the Afar region — one of the most geologically active zones in Africa — the volcano spewed massive columns of ash into the sky.

Residents of Afdera, a village near the eruption site, described the moment as terrifying. Local witness Ahmed Abdela said the ground trembled violently, “like a sudden bomb had been thrown,” leaving travellers stranded and forcing many to seek shelter from the ash blanket that quickly enveloped the region.

Remarkably, despite the scale of the eruption, no human casualties were reported. However, local authorities confirmed widespread ashfall that threatened pastoral communities, particularly livestock herders whose grazing lands were coated in grey volcanic dust, diminishing available fodder.

What Exactly Happened During the Eruption?

Unlike many eruptions that produce flowing lava, the Hayli Gubbi eruption was characterised by explosive emission of ash, gases, and fine fragments of volcanic material. No major lava flows were observed, but huge plumes containing rock particles, glass shards, sulphur dioxide (SO₂), and carbon dioxide shot approximately 14 km skyward.

Volcanologists pointed out that the fine particles and gases rose so high because the eruption superheated the surrounding air, causing it to rise rapidly and carry volcanic material into the upper layers of the atmosphere — between 15 km and 40 km above the Earth’s surface.

At these extreme altitudes, powerful air currents swiftly transported the ash cloud away from Ethiopia. The plume moved westward across the Red Sea with astonishing speed, steered by jet-stream winds.

A picture taken from a aircraft showing the difference between Volcanic Ash plume that lingers, moving and fading away from Indian region and Layer of Smog at the surface.

📸:@yash3101 pic.twitter.com/ArHNGL3cN2— IndiaMetSky Weather (@indiametsky) November 25, 2025

Scientists Explain: Why Did Hayli Gubbi Erupt After 12,000 Years?

The eruption took experts by surprise, especially because the volcano had no recorded activity throughout the Holocene — the geological epoch beginning roughly 12,000 years ago.

Arianna Soldati, volcanologist at North Carolina State University, noted that a long period of inactivity does not necessarily indicate a dead volcano. “As long as there are conditions for magma to form, a volcano can still erupt after 1,000 or even 10,000 years,” she said.

Hayli Gubbi sits within the East African Rift Zone — a region where the African and Arabian tectonic plates are slowly drifting apart by 0.4 to 0.6 inches each year. This tectonic separation creates pockets where magma can accumulate and eventually erupt.

Juliet Biggs, a leading earth scientist from the University of Bristol, challenged the assumption that the volcano had been inactive for millennia. Satellite data, she explained, hinted at recent lava movement and subtle uplift around the summit. She added that the giant “umbrella-shaped” eruption column seen on Sunday was extremely rare in this region, where shield volcanoes typically produce gentler lava flows.

Scientists had suspected something was brewing. In July, the nearby Erta Ale volcano erupted, triggering underground magma intrusion beneath Hayli Gubbi. Ground deformation and unusual white puffy clouds at the summit were recorded — early warning signs of impending activity.

Derek Keir, a geologist from the University of Southampton, happened to be in Ethiopia during the eruption and collected ash samples. These samples will help determine whether the volcano truly remained dormant for 12,000 years or had smaller undocumented eruptions.

How the Ash Clouds Travelled to India

Once the eruption column reached upper atmospheric levels, strong westerly winds carried the ash plume across the Red Sea. According to the India Meteorological Department (IMD), the ash travelled first towards Yemen and Oman before advancing over the Arabian Sea.

By Monday evening, the plume reached the Gujarat–Rajasthan region. Travelling at 120–130 kmph, it swept further northeast, crossing into Delhi, Haryana, and parts of western Uttar Pradesh around midnight. The ash cloud, forecasters said, was moving along the southwest-to-northeast trajectory, the same path along which it will eventually drift into China by Tuesday evening.

Weather trackers noted that the plume was situated between 25,000 and 45,000 feet — right in the altitude range where most commercial airlines fly.

⚠️ Ethiopia: The Hayli Gobi volcano erupted today for the first time in ten thousand years and sent ash up to a height of 15 km.🔥🔥 pic.twitter.com/aiPVhhO4rr— Dr. Fundji Benedict (@Fundji3) November 24, 2025

Why the Volcanic Ash Posed a Threat to Aircraft

Though the ash cloud hovered far above ground and posed no direct threat to human health, it created major hazards for aviation. Aircraft engines can suck in fine volcanic particles that melt and coat internal components, leading to engine failure. Ash clouds also reduce visibility, interfere with sensors, clog filters, and contaminate cabin air systems.

Recognising these risks, India’s Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGCA) issued urgent advisories:

-

Airlines must avoid volcanic ash-affected air routes and flight levels.

-

Flight planning and fuel routes must be adjusted based on real-time volcanic ash advisories.

-

Any suspected ash encounter — including odd engine behaviour or cabin odour — must be immediately reported.

The disruption was swift. Flights operated by Akasa Air, IndiGo, and KLM were cancelled or diverted. Akasa suspended flights to Jeddah, Kuwait, and Abu Dhabi on November 24 and 25. KLM cancelled its Amsterdam–Delhi (KL 871) and return Delhi–Amsterdam (KL 872) services. IndiGo diverted its Kannur–Abu Dhabi flight to Ahmedabad to avoid unsafe routes. SpiceJet and Air India also warned passengers of potential delays, asking travellers to monitor flight status closely.

Aviation officials said that if ash settled over Delhi or Jaipur by Tuesday, the impact on Indian aviation could be “severe.”

Did the Ash Cloud Worsen Air Pollution in India?

With Delhi’s air quality already in the “very poor” category — recording an AQI of 328 around India Gate on Tuesday morning — concerns grew about whether the volcanic ash would worsen pollution.

The IMD clarified that the ash plume was too high to directly affect surface-level air quality. IMD Director General Dr. Mrutyunjay Mohapatra explained that since the ash was 10 km or more above ground, “any significant impact on pollution is unlikely.” The ash mass behaves like cloud cover, making skies appear slightly darker or hazier and potentially causing marginal temperature increases.

Delhi’s poor air quality, officials stressed, was due to its usual winter pollution cycle — not the volcanic event.

How Long Will the Ash Plume Remain Over India?

The volcanic ash over India is expected to be short-lived. Atmospheric scientists say ash clouds disperse quickly, especially due to winds and precipitation. Clouds and rain help wash out fine particles, further reducing their density.

By Tuesday evening, the plume was already drifting toward eastern India and was expected to move fully into China by around 7:30 pm.

The Global Significance of the Hayli Gubbi Eruption

While the physical effects of the eruption may fade in days, the event marks an important geological moment. The Smithsonian Institution’s Global Volcanism Program previously recorded no eruptions from Hayli Gubbi during the Holocene. Sunday’s activity not only challenges those assumptions but also underscores how understudied and volatile the East African Rift remains.

As scientist Juliet Biggs noted, “It really just shows how understudied this region is.” The eruption may reshape scientific understanding of volcanic cycles in the area and provide vital data on deep Earth processes that trigger sudden explosive events even after thousands of years.

A Rare Eruption With Worldwide Ripples

From rural Ethiopia to major international airports in India, the Hayli Gubbi eruption has demonstrated how interconnected our world truly is. A geological event thousands of kilometres away can disrupt flight paths, alter skies over major cities, and spark global scientific curiosity.

With the ash cloud now moving out of India and the region returning to normal skies, attention shifts back to the Ethiopian highlands — where scientists are racing to unravel the mysteries of a volcano that woke up after 12,000 years.

With inputs from agencies

Image Source: Multiple agencies

© Copyright 2025. All Rights Reserved. Powered by Vygr Media.