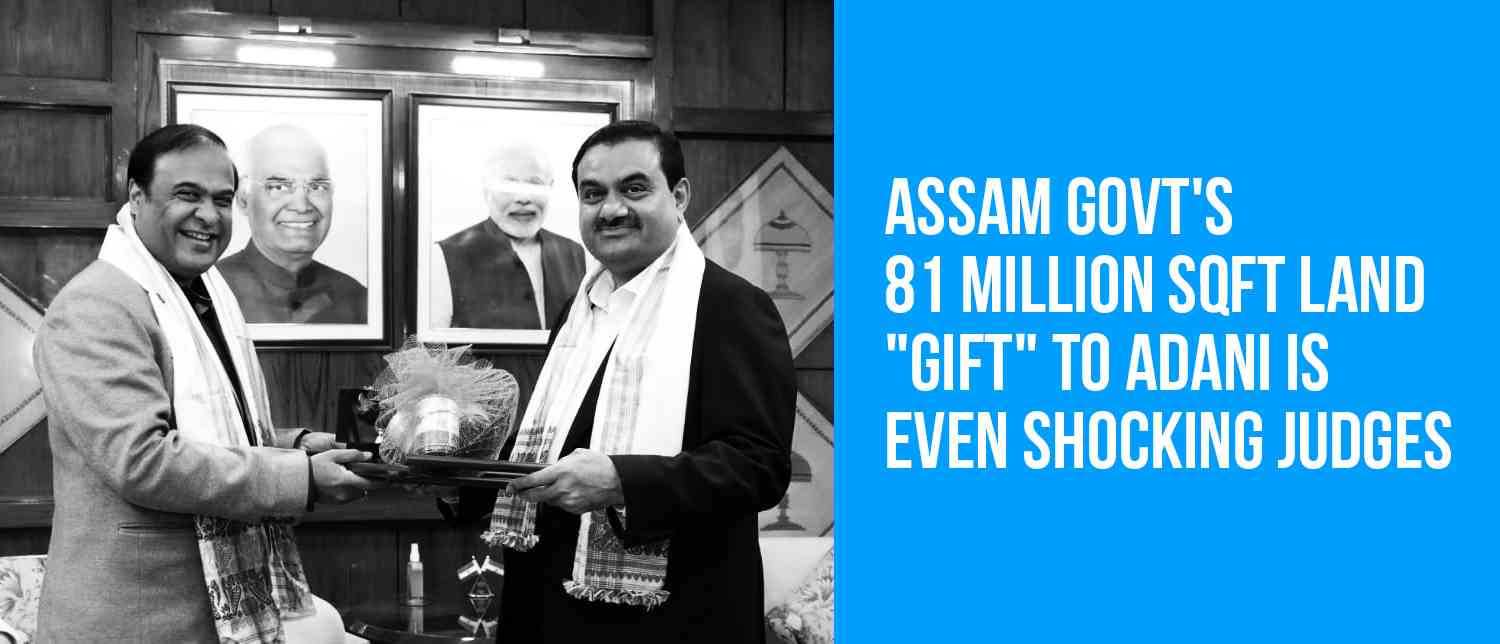

Assam’s Land “Gift” to Adani: When Development Becomes Dispossession

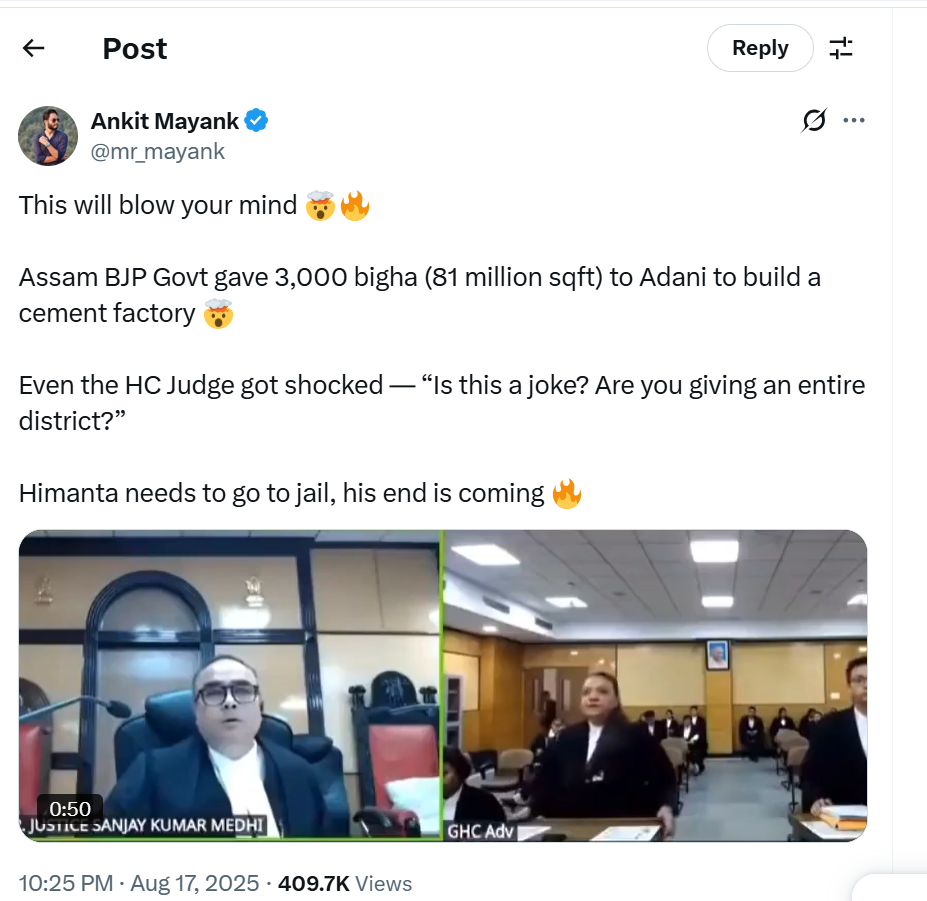

The Assam government’s decision to transfer nearly 3,000 bighas—approximately 81 million square feet—of land to the Adani Group has provoked outrage not only among citizens but also within the judiciary. To illustrate the sheer scale of this handover, one might say this was not an allotment but the creation of a private dominion. The shockwaves reached the courtroom, where even a High Court judge could not mask his incredulity, asking with cutting sarcasm: “Is this a joke? Are you giving away an entire district?” When the judiciary itself questions the rationality of a government decision in such stark terms, it suggests that the act has veered far beyond policy into the territory of absurdity.

This controversy is more than a land deal—it is emblematic of a deeper malaise. Under Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma, Assam appears to be sinking further into the quagmire of crony capitalism, where public assets are quietly transferred to corporate giants under the convenient banner of “development.” For ordinary citizens—farmers fighting to secure land titles, unemployed youth desperate for dignified work, and small entrepreneurs struggling to survive—the message is painfully clear: their aspirations are expendable, while the interests of billionaires are sacrosanct.

Industrialisation in a state such as Assam is not inherently undesirable. The region needs infrastructure, jobs, and opportunities. But genuine development cannot come at the cost of equity, transparency, and consent. Himanta’s model, however, seems to equate progress with favouring a handful of corporate patrons. The irony is bitter: cement factories and power plants for Adani, yet broken promises for the people.

The Growing Political Fallout

The political consequences are already becoming apparent. Public anger is no longer confined to activist circles; it is palpable in towns and villages, and now, legitimised by the judiciary’s sharp remarks. Himanta, once regarded as the BJP’s strongman in the Northeast, is being recast as a symbol of arrogance and corporate servitude.

Calls for accountability have grown so strident that some have even demanded legal action, framing the deal not merely as poor governance but as an outright betrayal of democratic trust. History shows that cronyism has destabilised governments before, and if unchecked, this scandal could mark the beginning of a steep decline for Sarma’s political fortunes. In democracies, leaders may push the boundaries of public patience, but the line between developmental policy and daylight robbery cannot be erased indefinitely.

A Parallel Scandal: The Kokrajhar Thermal Project

The outrage in Assam is not confined to the cement deal. In Kokrajhar’s Parbatjhora region, hundreds of villagers have staged months of protests against the proposed Adani thermal power project, alleging that the Bodoland Territorial Region (BTR) administration moved to hand over 3,400 bighas of land without even consulting the affected communities. Their fears are clear: the project threatens livelihoods, violates their constitutional protections, and erodes their ancestral rights over the land.

These protests are not new or isolated. For three months, residents have held rallies and demonstrations, insisting on their right to be heard. Their resistance highlights a glaring contradiction—while the government speaks the language of progress, it appears unwilling to engage with the very people whose lives will be transformed, if not destroyed, by such projects.

The controversy deepened when reports emerged that the land in question falls within the Paglijhora Protected Reserved Forest (PRF), legally recognised under the Forest (Conservation) Act. Even more strikingly, in April 2025, the state formally acknowledged forest rights for indigenous communities over nearly 280 hectares of this land under the Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006. Villages were converted into revenue settlements, a long overdue recognition of communities’ rightful claims.

Despite this, a letter dated 19 April 2025 (No. BTC/LR/803/2025/18) reportedly transferred the land to Adani Group, bypassing mandatory forest clearances and environmental approvals. If true, this is not simply administrative oversight—it constitutes a blatant violation of both the Forest Rights Act and the Forest (Conservation) Act. In bypassing these protections, the state has placed corporate interests above both ecological safeguards and the legal rights of indigenous people.

What is at Stake

At its core, the issue is not whether Assam should industrialise but how it should do so. Development that disregards legality, erases environmental safeguards, and sidelines the voices of local communities is neither sustainable nor democratic. Instead, it risks deepening inequalities, displacing vulnerable populations, and degrading fragile ecosystems.

For Himanta Biswa Sarma and his government, these deals may have been conceived as grand gestures to attract corporate investment. But politically, they risk backfiring, painting him as a leader who confuses private empires with public good. For the people of Assam, the message is even starker: their land, livelihoods, and future are being bartered away under the banner of progress.

As the courts, activists, and ordinary citizens raise their voices, the government finds itself on precarious ground. The more pressing question now is whether this “gift” to Adani will be remembered as a turning point—a moment when public outrage forced a reckoning between development and dispossession.

With inputs from agencies

Image Source: Multiple agencies

© Copyright 2025. All Rights Reserved. Powered by Vygr Media.