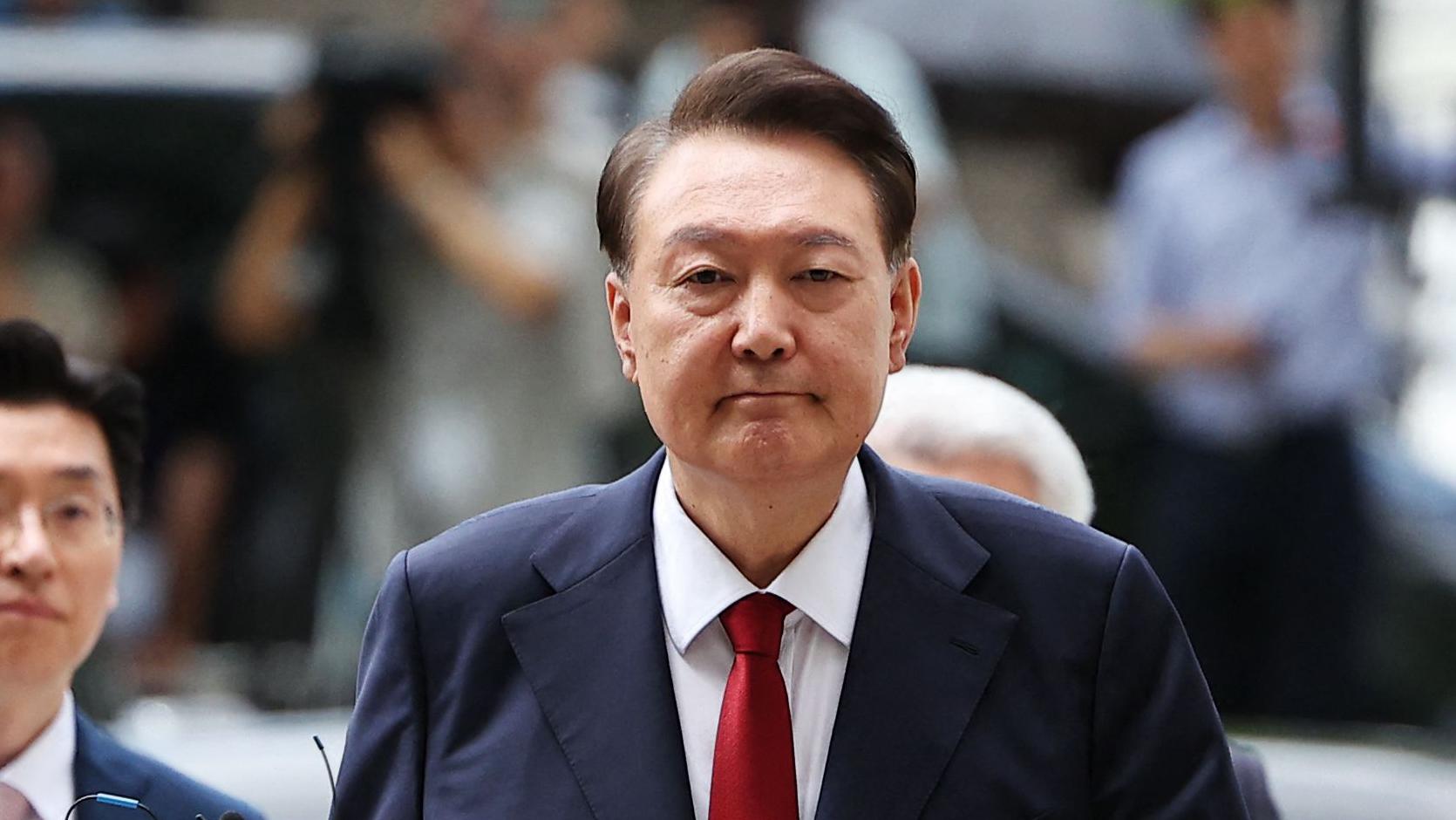

South Korea’s turbulent political history entered yet another defining chapter on Friday as a Seoul court sentenced former President Yoon Suk Yeol to five years in prison, marking the first criminal ruling connected to his dramatic and failed attempt to impose martial law in December 2024. The verdict, delivered by the Seoul Central District Court, found Yoon guilty on multiple charges, including abuse of power, obstruction of justice, falsification of official documents, and failure to follow constitutional procedures required for declaring martial law.

The ruling is the first of four criminal trials stemming from Yoon’s six-hour-long martial law declaration—an act that shook Asia’s fourth-largest economy, sparked nationwide protests, and ultimately led to his impeachment and removal from office. While the prison sentence is significant, it may prove only a precursor to even more severe legal consequences. In a separate case, prosecutors are seeking the death penalty for Yoon on charges of masterminding an insurrection, with a verdict expected in February.

A Historic Conviction of a Sitting President

Yoon Suk Yeol’s downfall is unprecedented in modern South Korean history. Although several former presidents have faced prosecution after leaving office, Yoon became the first sitting president to be arrested, following an extraordinary standoff with law enforcement in January last year.

The court ruled that Yoon had mobilised the presidential security service to block investigators from executing a legally issued arrest warrant. That warrant had been approved by the judiciary as part of an investigation into his controversial martial law decree. By ordering his bodyguards to shield him and physically prevent access to his residence, Yoon obstructed the lawful exercise of state authority.

“The defendant abused his enormous influence as president to prevent the execution of legitimate warrants,” said the lead judge of the three-justice panel during televised proceedings. The judge added that Yoon had effectively “privatised officials loyal to the Republic of Korea for personal safety and personal gain.”

Charges That Led to the Five-Year Sentence

The court found Yoon guilty on several key counts, each tied directly to the events surrounding his declaration of martial law and the chaotic aftermath that followed. These included:

-

Failing to follow due process before declaring martial law, including not consulting the full cabinet as required by law

-

Fabricating official documents, including drafting a false statement claiming the declaration had been endorsed by the prime minister and defence minister

-

Destroying potential criminal evidence, including wiping official phone data

-

Obstructing authorities from executing a valid arrest warrant by ordering the presidential security service to intervene

Judge Baek Dae-hyun emphasised the gravity of these actions, stating that Yoon had failed in his most fundamental duty as head of state.

“Despite having a duty, above all others, to uphold the Constitution and observe the rule of law as president, the defendant instead displayed an attitude that disregarded the Constitution,” the judge said. “The defendant’s culpability is extremely grave.”

Prosecutors had sought a 10-year prison sentence, citing Yoon’s lack of remorse and continued denial of wrongdoing. While the court ultimately handed down a five-year term, it noted that Yoon had “consistently shown no remorse,” a factor that could weigh heavily in upcoming trials.

Yoon’s Defense and Planned Appeal

Yoon has denied all charges and insists that his actions were lawful. His legal team argued that the arrest warrant itself was invalid and that investigators lacked the authority to probe or detain a sitting president. He also claimed that South Korean law does not explicitly require consultation with every cabinet member before exercising emergency powers.

Following the ruling, Yoon’s lawyer Yoo Jung-hwa said the former president would appeal.

“We express regret that the decision was made in a politicised manner,” she told reporters outside the courthouse.

Both prosecutors and the defence have seven days to file appeals.

The Martial Law Declaration That Shocked the Nation

Yoon’s declaration of martial law on December 3, 2024, stunned South Korea and the international community alike. The move came after his conservative People Power Party lost its parliamentary majority earlier that year, leaving his administration politically weakened.

Yoon justified the declaration by claiming the country was under siege from opposition forces and “anti-state” elements. He said the extraordinary measure was intended to restore democratic order and prevent government paralysis. He also made unproven allegations of electoral fraud.

However, the declaration immediately triggered alarm across the political spectrum. Members of parliament—including lawmakers from Yoon’s own party—rushed to the National Assembly, where they voted within hours to overturn the decree. Massive protests erupted nationwide as citizens took to the streets to defend democratic norms.

After just six hours, the martial law order was nullified.

From Impeachment to Arrest

The failed decree set off a rapid chain of events. Parliament soon impeached Yoon, suspending his presidential powers. In April, the Constitutional Court formally removed him from office, ruling that he had violated the duties entrusted to the presidency.

Rather than cooperate with investigators, Yoon barricaded himself inside his residential compound. He ordered the presidential security service to block authorities from arresting him, resulting in a tense standoff that lasted weeks.

A first attempt to detain him failed. Eventually, more than 3,000 police officers were deployed in a second operation that successfully breached the compound and arrested Yoon—an extraordinary moment that marked the first arrest of a sitting South Korean president.

Public Reaction Inside and Outside the Courtroom

On Friday, around 100 supporters gathered outside the Seoul Central District Court to watch the livestreamed verdict on a large screen. Some held red banners reading, “Yoon, again! Make Korea great again.” While several supporters shouted at the judge during the proceedings, others stood silently as the guilty verdicts were read.

The reaction reflected the deep divisions that continue to define South Korean politics. According to a survey conducted last December, nearly 30% of South Koreans did not believe Yoon’s martial law declaration amounted to an insurrection. While tens of thousands protested against him, smaller but vocal counter-protests rallied in his support.

What Comes Next: The Insurrection Trial

Friday’s ruling is only the beginning of Yoon’s legal reckoning. He still faces multiple trials, including charges related to campaign law violations and, most critically, insurrection.

Prosecutors argue that declaring martial law without justification constituted an attempt to overthrow constitutional order. For this charge alone, they have called for the death penalty, though legal experts note that capital punishment has not been carried out in South Korea for decades.

The verdict in the insurrection case is expected in February, and legal observers say Friday’s decision offers clues about how the remaining trials may unfold.

A New President, But Old Divisions

Six months after the failed martial law bid, South Korean voters elected Lee Jae Myung, leader of the liberal Democratic Party, in a decisive victory. Lee took office in June, pledging to restore stability and heal political divisions.

Yet Yoon’s ongoing trials continue to reopen old wounds, highlighting enduring ideological rifts and a pattern of presidential downfalls that has come to define South Korea’s modern political landscape.

The Troubled Legacy of South Korean Presidents

Yoon Suk Yeol is far from the first leader in South Korea to see his presidency end in scandal, prosecution, or tragedy.

-

Park Geun-hye, the country’s first female president and daughter of former dictator Park Chung-hee, was impeached in 2016 over corruption and abuse of power. Accused of receiving tens of millions of dollars from conglomerates like Samsung, sharing classified documents, and blacklisting critics, she was sentenced in 2021 to 20 years in prison. She was later pardoned by her successor, Moon Jae-in. Ironically, Yoon—then a Seoul prosecutor—played a key role in her investigation and incarceration.

-

Lee Myung-bak, who governed from 2008 to 2013, was sentenced in 2018 to 15 years in prison for corruption, including accepting bribes from Samsung. He was later pardoned by President Yoon in 2022.

-

Roh Moo-hyun, a liberal reformer and advocate of engagement with North Korea, died by suicide in 2009 amid a corruption investigation involving payments to his family.

-

Earlier decades were even more turbulent. Military strongman Chun Doo-hwan, infamous for the violent suppression of the 1980 Gwangju uprising, was sentenced to death in 1996 for treason and corruption, later commuted to life imprisonment. He and his successor Roh Tae-woo were eventually granted amnesty.

-

South Korea’s first president, Syngman Rhee, was forced into exile in 1960 after student-led protests over election fraud. Dictator Park Chung-hee, who seized power in a 1961 coup, was assassinated in 1979 by his own intelligence chief.

A Defining Moment for Korean Democracy

Yoon Suk Yeol’s conviction underscores both the fragility and resilience of South Korea’s democracy. His six-hour martial law attempt plunged the nation into crisis, but swift parliamentary action, public resistance, and judicial accountability ultimately prevailed.

“The accused has the duty to safeguard the constitution and law but turned his back on them,” the judge declared on Friday.

As Yoon prepares to appeal and await further verdicts—including one that could determine whether he spends decades in prison or faces the harshest penalty under Korean law—the country once again confronts a familiar question: how to reconcile strong institutions with a history of leaders who test their limits.

What remains clear is that Yoon’s legacy will not be defined by his presidency, but by the extraordinary legal reckoning that followed it—one that continues to reshape South Korea’s political future.

With inputs from agencies

Image Source: Multiple agencies

© Copyright 2025. All Rights Reserved. Powered by Vygr Media.